Twenty-four men wearing black caps and gowns strode across the stage of the Nash Correctional gym Dec. 15 to collect a bachelor of arts diploma in pastoral ministry.

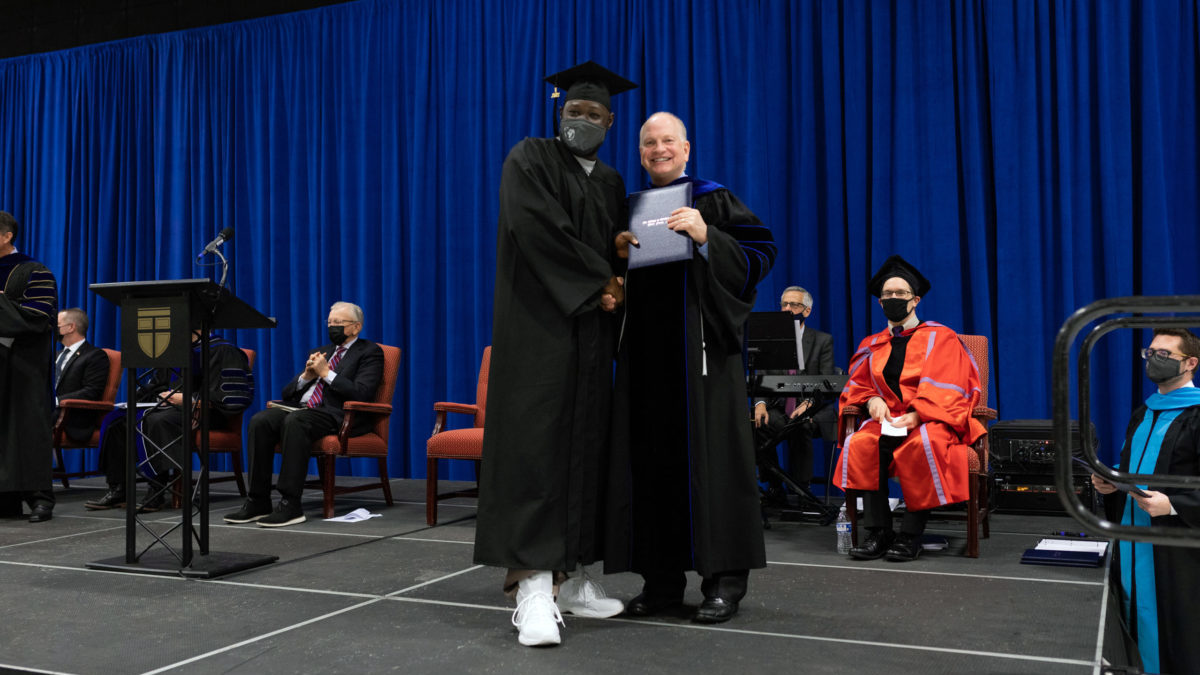

They shook hands with Danny Akin, president of the College at Southeastern, the undergraduate school of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, and posed for a photographer.

For these men, about half of whom will spend the rest of their lives in prison with no chance of parole, the march to the stage at the prison, about 50 miles east of Raleigh, was a high-water mark of their life behind bars.

They are among the inaugural class of inmates to earn a four-year degree from an accredited school and have spent long hours studying Hebrew, Greek, theology, counseling and the history of ideas.

All 24 inmates graduated with honors; three of the men had a perfect 4.0 grade point average. Now they will fan out across the state’s 55 prisons to serve the rest of their sentences ministering to other inmates.

“I can tell you from the bottom of my heart, I have never been more proud of any graduates that I have had the joy of presiding over,” an ebullient Akin said in his graduation address, noting he was “honored beyond words” to have his name inscribed on their diplomas.

National movement

The graduation marks a first for the North Carolina prison system, which to date offers no other in-person accredited bachelor’s program for some 30,000 state prisoners. But the degree program is part of a fledgling movement of evangelical seminaries, colleges and universities to rehabilitate prisoners through education.

There are at least 17 evangelical schools offering 23 degree programs at prisons across the country, according to the Prison Seminary Foundation, a Christian nonprofit that supports such efforts.

In most of them, seminary professors teach in-person and online to inmates with at least eight years left on their sentence. (Southeastern’s program requires inmates applying for the program to have a minimum of 12 years of incarceration left so they can complete their studies and gain experience serving as field ministers.)

At a time when some conservative evangelicals liken “social justice” to a postmodern ideology inconsistent with the Bible, the push for prison reform through education is quietly taking root.

“This could very well be a template for post-secondary higher education in prison,” said Julie Jailall, superintendent for prison education at the state’s Department of Public Safety. “It meets all expectations for what a prison education program should be.”

Jailall noted the program’s 80% rate of completion was particularly good outcome. The inaugural class included 30 men; three dropped out and three others will graduate with next year’s cohort. If they do, the rate of completion will rise to 90%.

In their new positions as field ministers, the men will not be expected to preach or convert other inmates to Christianity. The prison system cannot promote one faith over others, said Jailall. But they will be expected to counsel and mentor inmates and to encourage them to seek out opportunities to better themselves. Some will also be co-teaching a class called “Thinking for a Change,” a cognitive–behavioral curriculum developed by the National Institute of Corrections. The efforts are intended create a calmer prison environment and reduce violence.

For their efforts, the inmates will earn $1 a day.

‘I’ve grown out of myself’

Kirston Marshall Angell, a 32-year-old inmate who graduated summa cum laude, said he was “ecstatic” and happy to head to a maximum security prison in the western part of the state where he is expected to work with new inmates, ages 18–25, adjusting to life in prison for the first time.

“I’ve grown out of myself,’ said Angell, who is serving a 40-year sentence for second-degree murder. “I’ve learned to set myself aside and favor others. That’s what this program has called us to.”

Angell’s education, as well as that of his classmates, was paid for by a grant from Game Plan for Life, a Christian ministry founded by former NFL football coach and current auto racing team owner Joe Gibbs, who partnered with the College at Southeastern to launch the degree program.

It costs Southeastern $500,000 a year to run the prison program. The college has also secured supplemental funding from the Sunshine Lady Foundation and the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina, said Seth Bible, director of the prison program and an assistant professor of ethics and the history of ideas at Southeastern.

The support of these and other funders is critical to the program, he said.

“I ask on the first day: ‘How many of you never thought you’d have the opportunity to get a four-year college degree?'” said Bible. “Without fail, for four straight years, 90% of the people in class will raise their hand. They say they didn’t have strong parental influence or were influenced by drugs or gangs and never had anyone believe in them, or they’ve never believed in themselves.”

The opportunity, he said, can give inmates a new perspective. “The moment you begin to tell someone that they have value, first in the eyes of God and in your eyes as well. And, then you tell them, not only do I think you have value, but the people who support this program think you have value — that, in itself, is transformative.”

Prison education is expected to receive a big boost in June 2023 when inmates at many federal and state prisons will qualify for Pell grants for college education. In 2020, Congress lifted a ban on federal financial aid to prisoners that had been in place since 1994.

Ten North Carolina schools have recently formed a Prison Education Collaborative to begin thinking about ways to increase the number and variety of degree programs in the prisons. Campbell University plans to graduate two dozen inmates with a bachelor of arts or bachelor of science degree in communication studies with a minor in addiction disorders in 2023.

‘Sweeping the country’

But for now, the evangelical programs are the most prevalent, especially across the Southern U.S., where evangelicals are dominant. Southeastern recently started a similar program at a women’s prison in Raleigh.

“It’s sweeping the country,” said Denny Autrey, director of operations for the Prison Seminaries Foundation. “More wardens and directors of prisons are looking for ways to change the tide of crime inside and help these guys when they do get out so they don’t come back in. It’s an educational program that impacts the heart and mind.”

Few of these educational programs address problems associated with the carceral state, such as racial disparities or the ways the justice system disproportionately punishes people who are poor, mentally ill and addicted. The United States has the highest incarceration rate of any country in the world.

One program that does is North Park Theological Seminary’s School of Restorative Arts, which offers a master’s degree in restorative justice ministry. The program, run at two Illinois prisons (one for men and another for women), includes classes on conflict de-escalation, race relations, trauma, healing and restorative justice. Its faculty also advocates for students’ release and prison abolition more generally.

“A lot of programs are training people to be missionaries on the inside, but they’re not advocating for their freedom,” said Michelle Clifton-Soderstrom, director of the program and the dean of faculty at North Park’s seminary. “We are not of that mindset. We recognize there are better ways to address violence and mass incarceration.”

At the graduation ceremony in North Carolina, which was followed by a catered lunch for graduates and their families, Southeastern leaders made it clear they wanted graduates to be “ambassadors for Christ,” in the words of Joe Gibbs and Danny Akin at the graduation ceremony.

‘Life-changing light of Jesus’

Akin reiterated that Southeastern is a seminary whose core purpose is to spread the faith.

Speaking to the graduates, Akin said: “You get to take the life-changing light of the gospel of Jesus Christ to those who have value, men for whom Christ died,” Akin said.

Loren Hammonds, a 43-year-old inmate serving a sentence of life without parole, said that’s exactly what he hopes to do. Hammonds, who held his mother’s hand as he sat with his parents, shortly after the graduation, said he will be sent to a hospice-care ward at a prison 40 miles from Charlotte where he will offer comfort and companionship to terminally ill men who will spend their final days in a cell block.

“I want to give them hope,” he said, “and introduce them to the gospel.”

Share with others: