Leta Head was shocked and speechless when she saw “Alzheimer’s disease” listed as the cause of death on her mother’s death certificate.

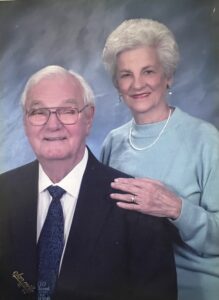

Frances “Nanny” Hobdy lived with chronic lung infections for more than 30 years. Despite this fact, she finished working as a nurse at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and led a vibrant and independent life, handling her own finances and dedicating herself to her family and faith.

In the testimony she penned before her death, Nanny wrote that she “always wanted to be a soul winner.” She shared the gospel with everyone, including her patients.

During her final year of life, Nanny battled bronchiectasis (damaged, clogged airways), which was caused by the recurring infections. She persevered through hospitalization, home health care and hospice care until her death on Jan. 29, 2023, at age 89.

Nanny had never been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s by any physician, nor had any health care professional ever suggested the possibility of Alzheimer’s to Head or her family. The one brain scan performed on Nanny was assessed to be normal for someone her age.

Multiple providers indicated Nanny was suffering from delirium — a sudden-onset, fluctuating cognitive disorder likely caused by the infection that raged in her lungs. Her white blood cell count was extremely elevated at intervals, and despite administration of IV antibiotics, it never returned to normal levels after her initial hospitalization in February 2022.

Cause of death

So how was Nanny’s cause of death determined to be Alzheimer’s? When Head raised this question with the agency that administered her mother’s home health and hospice care, she had no idea what kind of struggle was ahead.

The prevalence of errors in modern medical records is well documented by publications like JAMA, The Journal of the American Medical Association. But in today’s era of digital recordkeeping and accessible patient portals, these mistakes may also be more easily noticed and reported by patients and their caregivers.

In Head’s case, she requested physical copies of Nanny’s health records and made a key discovery. Months into her mother’s course of treatment — late in September 2022 — a visiting home health nurse notated Alzheimer’s as an underlying condition in her report.

Somehow, during the insurance billing process, the home health agency switched Nanny’s primary diagnosis of “bronchiectasis with acute lower respiratory infection” with the unverified Alzheimer’s diagnosis. In other words, her cause of death was decided based on an assumption made during one home health visit and a coding error.

This issue seemed simple enough to sort out. But Head’s attempt to do so was met with months of resistance from the home health agency, which refused to concede its error. It took almost a year for Head to reach a resolution, and in the end she had to escalate her concerns to the CEO of the agency.

Head’s primary motivation was to honor her mother’s legacy.

“My mother lived her life based on honor and integrity,” she said. “My goal in all this is that no one should ever have to go through this when they’re grieving the loss of a loved one.”

Family health history was also on Head’s mind. She didn’t want her mother’s death certificate to mislead future family members who might seek medical answers through genetic genealogy. Nanny’s records needed to reflect an accurate cause of death — for her loved ones in the present and for generations to come.

Unfortunately, while reviewing her mother’s records, Head found another problem. In certain parts of the file, Head’s Social Security number had somehow been used in place of Nanny’s. Head reached out to the Social Security Administration to make sure she herself hadn’t been reported deceased or dying and to ensure no claims had been filed using her identity.

Ultimately, it was the misuse of Head’s Social Security number — a violation of privacy laws — that likely helped resolve the error on Nanny’s death certificate.

Head shares her story so others will know the value of ensuring that their medical history is correct.

Based on her experience, she shares these two tips:

1. Always ask for records.

Medical providers keep extensive files and notes on their patients. As a patient, you may never see more than a summary, but you have a right to inspect, review and receive a copy of your medical and billing records.

When it comes to home health care, patients and their families often have more limited access to medical records and nurses’ notes. Caregivers like Head are often handed a tablet at the end of each visit and asked to sign, mostly as evidence of services rendered. Visit notes may not be displayed on the device at all.

“There’s nothing above [your signature] or below it,” Head recalled. “You don’t really know what you’re signing.”

Home health agencies are obligated to provide records upon request. To ensure the best possible care for your loved ones, it’s important to ask for digital or physical copies of notes from each visit in a timely manner. Good record-keeping is the best way to avoid mistakes and make sure you and your health care provider are on the same page. Taking that extra step will help protect you and the agency you’re working with from future disputes. “Trust but verify,” Head recommends.

2. Be an advocate.

In seeking to honor her mother’s legacy, Head faced significant challenges. “I got very discouraged at times and really wanted to give up.” But her decision to stay the course was deeply rooted in her love for Nanny and for God’s Word. “That’s the only one of the Ten Commandments that has a promise: ‘Honor your father and your mother, that your days may be long upon in the land.’” Every phone call, every email, every week of research and sifting through hundreds of pages of records was worth it for Head.

Older adults need our advocacy in times of illness or injury when they are often vulnerable and unable to communicate their needs. Patient and family education about delirium is especially vital. Cases of assumed Alzheimer’s are all too common among elderly patients — especially those recovering from surgery or being treated for infection, traumatic injury or medication reactions.

As the National Institutes of Health explains, “The incidence of delirium increases with age,” and that incidence ranges from “8% to 17% in older patients presenting to the emergency center to as high as 40% among nursing home residents.” It’s not unusual for health care workers to make assumptions about dementia in older adults, even without knowing their prior health history.

The NIH outlines the inherent danger of such assumptions. “Differentiating delirium and dementia is critically important” since “[t]he two are distinct pathologic processes with different management and prognoses.” Compared to dementia, delirium is far more “preventable and reversible.”

Head hopes that by sharing Nanny’s story, she might help others get better care for their loved ones and be more aware of the accuracy of their medical records.

“If my mother’s story can make a difference in just one person’s life,” Head began, “it will have all been worth it.”

Share with others: