When Michaela Sanderson Guthrie was 11 years old, a social services caseworker gave her an unimaginable choice — live with a family member or enter foster care.

“My sister looked at me and I said ‘foster care.’ What 11-year-old would say that? But looking back, I totally believe it was the Lord speaking through me,” Guthrie said. “I knew nothing would change if we went to live with my grandmother and I didn’t want that for us.”

For years, Michaela and her siblings — twin sister Danielle, older sister Mary Elizabeth and brother Jesse — had witnessed drug abuse and domestic violence. Her father was a drug dealer and random strangers came in and out of their home regularly. “Home” changed often and most of the places they lived were roach-infested, molded and run-down. Some had no running water or heat. “I went to seven elementary schools because we spent a lot of time running from my dad,” she said.

Emotional time

The summer after her 2nd grade school year, someone took notice. Michaela and her siblings moved in with an aunt and uncle. In addition to the strain of her family’s struggles, Michaela’s older sister, Mary Elizabeth, got sick.

Eight years older than Michaela and Danielle, Mary Elizabeth had mothered her younger siblings for most of their lives. The disease took her ability to eat and required removal of one of her lungs. When Mary Elizabeth was just 16, pneumonia took her life.

By this time, Michaela and her siblings were living with their mother once again. She had taken parenting classes and seemed to be on a better path. Mary Elizabeth’s death was hard on all of them and it seemed to exacerbate their mother’s bipolar disorder. Her struggle intensified, culminating in a terrible night when Michaela was in the 6th grade.

“She woke me up, asking for the gun, which I had hidden from her. She wanted to know where it was and finally I told her,” Michaela said. “I woke up again when I heard the gun cock. I ran to her room and tried to convince her not to shoot herself. I was there when she did.”

Michaela’s mother shot herself in the stomach right in front of her daughter. Michaela ran across the street to the nearby volunteer fire department to get help. Her mom survived but the shooting was the turning point in the girls’ young lives. And it meant the brother would be separate from his sisters.

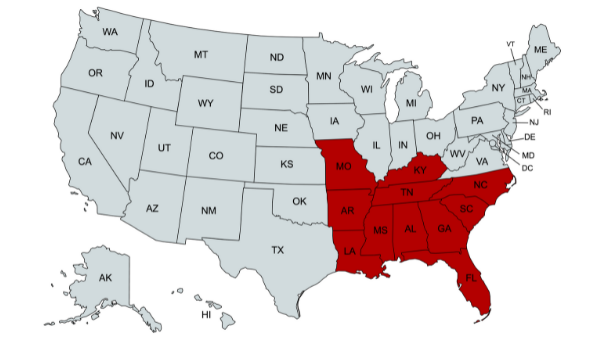

After speaking with the social worker, the twin sisters moved into the Alabama Baptist Children’s Homes (ABCH) Gardendale Campus Care home (now Family Care Home). For the next two years, Michaela and Danielle experienced the consistent love of their house parents, June and Woody Lafontaine. They also learned what it meant to be responsible members of a household.

“We learned a lot of life skills by doing chores, including vacuuming our rooms before school and washing our clothes,” Michaela recalled. “We had never even had a washer and dryer.”

Some of the rules, like wearing socks and shoes to meals, seemed silly to a young girl.

“I’m not sure how much I loved it then,” Michaela said with a laugh. “But it was such a blessing. Of all the places we could have been placed, that was a great place.”

On the girls’ 13th birthday, they found a permanent home with cousins Stacy and Johnny Brooks. The Brookses had made the decision to be foster parents for the girls earlier but a delay in processing their fingerprints postponed placement. Looking back, Stacy Brooks believes the delay was part of God’s plan.

‘Where they needed to be’

“The time the girls spent at the Children’s Homes was a godsend for them. They were taught so many things, like doing homework and chores. Their house parents laid down ground rules that made the transition easier into our home. I am convinced the Lord was protecting them. It was where they needed to be,” Stacy Brooks said.

It was also while living at the Children’s Home that Michaela started going to Gardendale First Baptist Church. Her youth group and student pastor became a big part of her support team, especially after her mother died suddenly from a seizure shortly after Michaela moved in with the Brookses.

Unbeknownst to Michaela, ABCH was in the background too. In fact, ABCH wanted to do something for the girls after their mother’s death and purchased an urn for her ashes as a gift to the family.

Year after year, ABCH representatives contacted the Brooks family at Christmas to get a wish list.

“They went above and beyond,” Stacy Brooks said. “They could have said ‘we’re done with them’ but any way ABCH could help, they did.” When Michaela graduated from high school with honors and headed to the University of Alabama to earn a degree in social work, ABCH was there for her once again. Though almost all of her college expenses were paid for through scholarships and financial aid, additional assistance from ABCH helped Michaela concentrate fully on her academic work.

In four years, she completed her undergraduate work and a master’s degree in social work and graduated debt-free, despite being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) at the age of 19.

Helping students like Michaela transition into adulthood is possible through the generous support of donors, according to Michael Smith, ABCH chief operations officer for North Alabama, who works with job training and college assistance programs.

Nationally, only about 2 percent of children coming out of foster care earn a college degree. In contrast, about 70 percent of students transitioning out of ABCH care graduate from college, Smith said.

That success rate has gotten national attention and Smith said it has everything to do with the structure of the program.

“We have a ‘College Contract’ that lays out what ABCH will do for the student and what the student is expected to do to maintain standing in (our) program,” Smith said.

On average, 4–5 children in ABCH care graduate from high school each year. Not every student is college-bound, of course. Some students participate in technical certification or job training programs. Regardless of their interests and abilities, ABCH works to help each student transition from care to independence successfully.

‘Learning about Lord’

“We always try to individualize to what will help each child have the most success,” Smith said.

In the years since graduation, Michaela has married her high school sweetheart, Jason, who was part of the youth group at Gardendale First Baptist. Her MS is in remission and Michaela works as an assessment coordinator for Georgia Cares, a nonprofit that works with youth who have been sexually exploited. The couple lives in the Atlanta area where they are part of a local church. Michaela says they are “constantly growing and still learning about the Lord,” a desire kindled in part by her time at ABCH.

“My husband is a great spiritual leader for me and the group home helped build that foundation by showing me what it looked like to have a spiritual leader in the home,” she said.

Most recently, Michaela’s story was featured in “Be the One: Six True Stories of Teens Overcoming Hardship with Hope,” by veteran journalist Byron Pitts, co-anchor of ABC’s Nightline. She also will be featured on Nightline in late June or early July.

Michaela met Pitts when she was chosen from among 50,000 applicants nationally as 1 of 104 recipients of the Horatio Alger Scholarship and was asked to share her story at the organization’s annual convention in Washington.

As Michaela works with children coming out of difficult situations, she can see parallels to her own childhood and she knows what made the difference for her.

“Looking back, one of the biggest things for resilience is a support network,” she said. “From an early age, I had the mindset that I wasn’t going to fall into the same pattern as my parents. I had Stacy and Johnny and ABCH — and their support has made all the difference.”

Share with others: