Diabetic church members and guests find meals at Baptist churches either obstacles to overcome or opportunities to enjoy.

Whether a Wednesday night supper, a festive dessert contest, a Sunday night pizza outing for youth or an after-church rush to Sunday lunch at a restaurant, food is an inescapable fact of Baptist life.

“I live a pretty good life to be a diabetic,” said Kathleen P. Rushian, a member of Taylor Road Baptist Church, Montgomery. Rushian, in her late 70s, was diagnosed with Type II diabetes in July 1990 when she was 63.

“I went on my diet, watched what I ate and asked the Lord to help me quit eating sweets,” she said.

Rushian takes Humalog, tests her blood sugar four times a day, is active and enjoys church fellowships. “I usually can eat a little of most everything, except sweets. I just eat a small serving,” she said.

Rushian, who is 5 feet 9 inches tall and about 179 pounds, said, “I’m just doing great.” She goes on outings like touring the state capitol and traveling to various events with friends, family or church members.

To help diabetics stay active and healthy kitchen managers and fellowship organizers can offer healthier food for everyone, since healthy food for a diabetic depends partly on the way it is prepared.

Churches that use high-fat methods of cooking or opt for prepackaged or processed foods do diabetics and other health-conscious people a great disservice.

Eventually, churches and the rest of society bears the burden of the economic cost of bad health from poor diets, diabetes educators say.

A good diet for a diabetic is a good diet for anyone, they contend.

That is because the diet promotes good general health, with nutritional ideas that can reduce the risk of heart disease, stroke and a host of other medical complications in adults.

Meals for diabetics are not as inflexible as they used to be, according to Pam Green, manager of the Baptist Health Center for Diabetes in Montgomery and Certified Diabetes Educator.

Green said that in today’s treatment plans for diabetics, the management of total carbohydrates, rather than strictly prohibiting all sugar, is the popular thought. How many carbohydrates a diabetic eats is coordinated with the amount of insulin they inject and how physically active they are.

In 1994 the ADA changed its recommendations for dietary guidelines from a no-sugar diet to including small amounts of sugar in diabetic meal planning.

“In 1994 we stopped telling people that they could never have sugar. We count total carbohydrates, looking at the line on the nutritional panel marked ‘total carbohydrates.’

Sugar is a carbohydrate, and its content is listed in grams per serving under the heading of carbohydrates,” said Green.

It is also important for diabetics to limit their intake of saturated fat.

A great Web site that provides a huge selection of low-carbohydrate recipes seems to work best from Google or Ask Jeeves search engines.

Enter the following search term exactly as: Low Carbohydrate Cooking-Recipes. The first result, which includes “camacdonald” in a lengthy address line should be the one.

Though diabetics can eat traditional foods prepared in a healthy way, there is a wide array of low-sugar and sugar-free foods and drinks widely available.

Unlike a few years ago, the food industry today offers literally thousands of traditional products in diabetic-friendly versions. You name it — lemonade, chocolate chip cookies, strawberry shortcake, cheesecake, ice cream — these are just a few of the choices that are growing in America’s supermarkets.

Millions of health-conscious Americans — diabetics among them — are seeking a healthier diet that is lower in sugar, saturated fat and cholesterol, thus creating a substantial market for these products.

Packaged Facts (PF), a division of MarketResearch.com, estimates that annual retail sales of sugar-substitute and low-sugar food and beverage products exceeded $7.9 billion in recent years.

“Marketers are developing new products in response to both an increased consumer demand for healthier food alternatives and an increasing number of diabetics,” PF states in a report titled “The U.S. Market for Sugar-Substitute and Low-Sugar Foods.”

Sucralose, for example, earned FDA approval in April 1998, becoming the first new artificial sweetener to win FDA approval in 10 years. Sold under the name Splenda, it is made by McNeil Specialty Products Co., a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson.

It is derived from real sugar through processes that change sugar’s chemical composition. Splenda is effective in baking, where many older artificial sweeteners cannot be used for baking.

Many drinks and food items have switched to sweetening products with Splenda.

Carefully reading food labels is key to knowing what you’re getting. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration sets requirements for words such as “no added sugar” or “sugar free.”

For a product to be labeled “sugar free,” it must have fewer than 0.5 grams of sugar per serving, according to a statement from Paula Kurtzweil, part of the public affairs staff of The Food and Drug Administration.

“No added sugar” refers to the nutritive or natural sugars found in foods being the only sugars present. For example, a can of sliced peaches labeled “no added sugar” should have only those sugars naturally occurring in the peaches.

“ ‘Sugar free’ and ‘no added sugar’ signal a reduction in calories from sugars only, not from fat, protein and other carbohydrates,” Kurtzweil said.

“If the total calories are reduced, the claim must be accompanied by a ‘low-calorie’ or ‘reduced-calorie’ claim,” she said.

A beneficial food label tip is to know how to find out the “net impact carbohydrates” or “effective carbohydrate count,” according to Andrew S. DiMino, president of CarbSmart, a company listing the nutritional facts and ingredients on more than 950 products.

Not all carbohydrates are absorbed into the body and treated as calories by the body. Dietary fiber, for instance, widely found in plants, fruits, vegetables, bran and other food sources, is not absorbed and may be subtracted from the total carb count, he said.

His formula to determine the total carbohydrates that will actually have a raising effect on blood sugar is to subtract from the total carbohydrates on the label the following: dietary fiber, sugar alcohols, hydrogenated starch Hydrolysate and glycerine. The result should be the total grams of carbohydrates that have an impact on blood sugar.

The FDA is now requiring the industry to be consistent with its carbohydrate labels, showing all carbohydrates, then showing those that DiMinos says can be subtracted out for a net carb count. It is net carbs that have a direct effect on raisin blood sugar levels. Previously some manufacturers listed a total carb count that reflected the non-blood sugar-impacting carbohydrates already subtracted. This was on the nutrition label. Packaging on many new labels shows the net carbs prominently on the front or top of the product’s container.

Conquering the mysteries of cooking and eating carbs

Related Posts

FDA, researchers seek methods of early detection of Alzheimer’s

October 1, 2024

A new blood test could help doctors diagnose Alzheimer’s disease more accurately in a primary care setting, leading to crucial

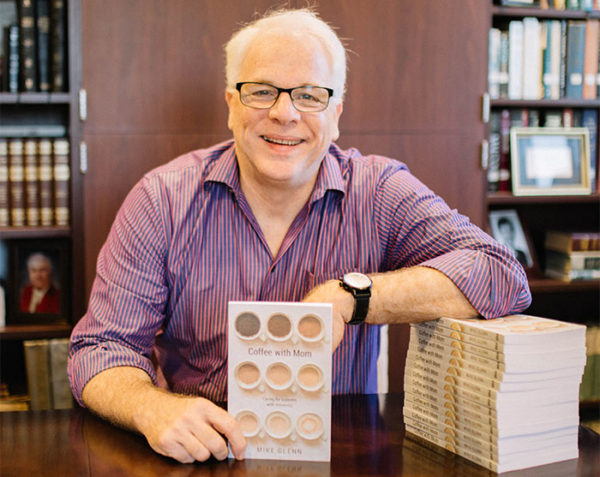

Alzheimer’s, dementia: Pastor shares lessons learned

August 12, 2019

As a minister for more than 40 years, Mike Glenn walked through the valley of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease with

Shame isolates, destroys community, psychiatrist says

October 13, 2016

Nobody needs a psychiatrist to explain what shame feels like — we all know, said Curt Thompson, a noted psychiatrist

Prenatal classes catalyst for new life, faith, churches

January 22, 2015

The young woman gingerly crawls off a motor scooter, grateful for the ride. Before, Kalliyan Seng could make the two-mile

Share with others: