Let’s face it. No one likes to discuss or plan death — but it is a part of life. The question of how to plan for end-of-life wishes is a legitimate one.

According to Alabama law, you have the right to decide about your medical care, but if you are very sick or badly hurt, you may not be able to say what medical care you want.

In the late ’90s, states began amending their laws and forms. Alabama was one of the first to adopt a more extensive Advance Health Care Directive and to amend its Natural Death Act. The form passed by the Alabama Legislature in 1997 proved too long and complicated, and lawmakers passed a shorter, simpler version in the spring of 2001, effective as of Aug. 1, 2001.

An advance directive is used to tell your doctor and family what kind of medical care you want if you are too sick or hurt to talk or make decisions. If you do not have one, certain members of your family will have to decide on your care.

Jim Wilson, chaplain at Northeast Alabama Regional Medical Center in Anniston, said, “It is very important for all of us to think about what we would want in those circumstances and talk to our families.” Wilson, who has been a chaplain for 35 years, seven of those in Anniston, gets called to various situations to serve as a moderator or someone who will listen.

Big issues arise when planning for the end of life. Attitudes and beliefs about religion, pain, suffering, loss of consciousness and leaving behind loved ones come into play.

Wilson, a retired pastor and member of First Baptist Church, Jacksonville, said spiritual questions come into play with some families. “Frequently people have to make decisions in a traumatic situation — that can make it much harder,” he said. “It’s like a combat situation. They (hospital staff) deal with life and death every day.

“Sometimes families are not prepared to let [loved ones] go,” he said. “That’s hard on the staff. It’s up to the family to decide.”

Caregiver.org, the Web site of Family Caregiver Alliance, offers several helpful tips for end-of-life planning. Some of these include:

-Who do you want to make decisions for you if you are not able to make your own, both on financial matters and health care decisions? The same person may not be right for both.

-What medical treatments and care are acceptable to you? Are there some that you fear?

-Do you wish to be resuscitated if you stop breathing and/or your heart stops?

-Do you want to be hospitalized or stay at home, or somewhere else, if you are seriously or terminally ill?

-How will your care be paid for? Do you have adequate insurance? What might you have overlooked that will be costly later at a time when your loved ones are distracted by grief?

-What happens when a person dies? Do you want to know more about what might happen? Will your loved ones be prepared for the decisions they may have to make?

Another issue that often arises is the financial aspect of end-of-life planning. According to www.caregiver.org, sometimes the place to begin taking control of planning is in the estate and finances because the content is more concrete. The Web site suggests that people have a valid, up-to-date will or trust documents, if desired or needed. It also suggests all insurance information (medical, long-term care, life and special needs policies) be kept in an accessible place. Tell a trusted person where the documents are located.

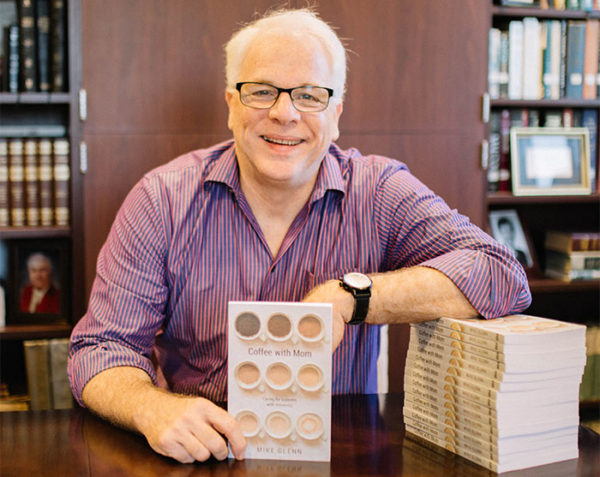

Author Hank Dunn, a nursing home and hospice chaplain for 17 years, has researched medical literature and presented the facts in “Hard Choices.” The book covers medical treatment decisions, CPR (resuscitation efforts), artificial feeding and shifting to a hospice approach. There also are sections on ventilators, dialysis, antibiotics and pain control.

According to the Hard Choices Web site, www.hardchoices.com, the book is not just for the elderly but for anyone facing a life-threatening illness. It is wise to prepare an advance directive so that medical personnel and your loved ones will know what care and services you prefer and what treatment you would refuse, in the event that you are unable to communicate your wishes. You also can designate the person, or more than one person, whom you would like to make decisions on your behalf. In a surprising number of families, there is a disagreement over what a very ill relative would prefer. The advance directive makes your wishes clear.

“It’s very important for all of us to think about what we would want in those circumstances and talk to our families,” Wilson said.

Share with others: