By Mark Rathel, Ph.D.

Professor of Theology and Philosophy

Baptist College of Florida

In numerous places, a “War of the Bibles” is a 21st-century reality. Some Christians favor the King James translation while other Christians prefer a newer translation.

But this debate is not a new phenomenon. Before the publication of the Authorized Version, also known as the King James Version, a conflict developed over the issue of which English translation was best. The Bishops Bible, the Great Bible, Miles Coverdale’s translation and William Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament from Greek into English is a partial list of English translations at the time the Pilgrims arrived in the early seventeenth century.

The Pilgrims that landed near Plymouth Rock in 1620 brought with them from England a biblical translation published in 1560. The Geneva Bible was the first full translation of the Bible from Hebrew and Greek into the English language.

‘Breeches Bible’

The Geneva Bible at times was nicknamed the “Breeches Bible” because of its translation of Genesis 3:7: “Then the eyes of them bothe were opened & they knewe that they were naked, and they sewed figtreee leaves together, and made themselves “breeches.”

How did this English Bible produced in Geneva, Switzerland, become the Bible carried to the New World by the Pilgrims?

Due to the persecution of Protestants by Mary I, the Catholic queen of England and Scotland often called “Bloody Mary,” numerous Protestants fled to Geneva.

John Knox of Scotland served as the pastor of a church of Englishmen and Scots. A branch of the persecuted Protestants called themselves “Pilgrims,” borrowing from the language of Hebrews 11:13: “All these died in the faith, and received not the promises, but acknowledged them from a far off, and believed them, and received them thankfully, and confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth.”

‘Bloody Mary’

Queen Mary prohibited the printing of Bibles in England. The persecution inflicted by Mary resulted in some of the best biblical linguists of the day departing England for Geneva. These noteworthy scholars functioned as key translators of the Geneva Bible. Some of the persecuted Pilgrims returned to England after Queen Mary’s death and dedicated the translation to Queen Elizabeth.

The stated purpose of the translators as set forth in the preface was to “set forth the purity of the word and right sense of the Holy Ghost for the edifying of the believers in faith and charity.”

The Geneva Bible was a Bible of firsts.

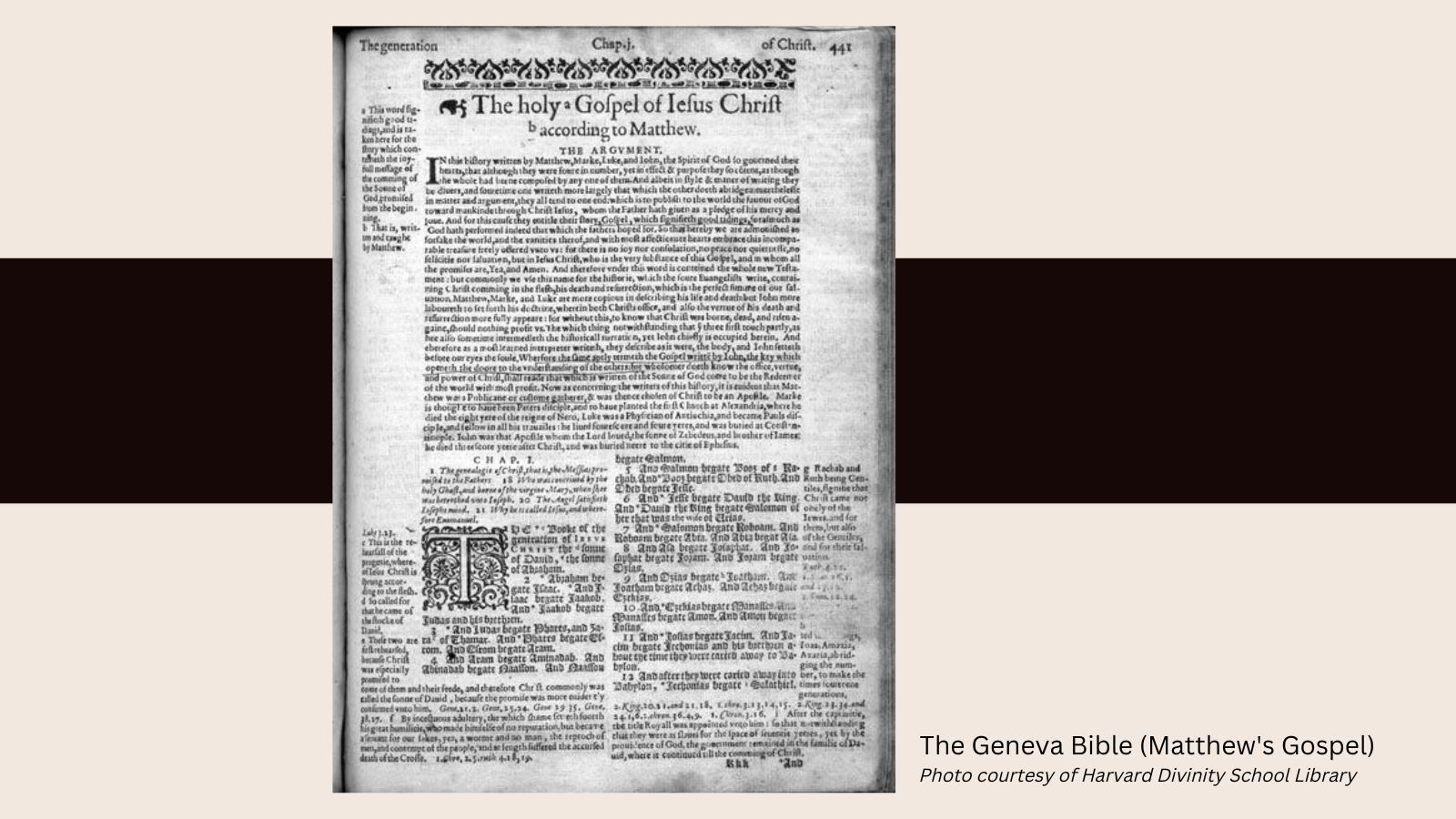

- The Geneva Bible of the Pilgrims was the first English translation to use verse numbers.

- The Geneva Bible contains five maps, a biblical dictionary, a glossary of biblical names and the meaning of the names with an exhortation for parents to choose the names of their children from the list to give their children testimonies by their biblical names.

- The Geneva Bible also contained a chronological chart.

The most noteworthy feature of the Geneva Bible was the marginal notes explaining the Scripture. Perhaps because of the Geneva Bible, England’s King James in 1604 prohibited the use of marginal notes in Bibles because he regarded marginal notes as being “untrue, seditious, savoring too much of dangerous and treacherous conceits.”

Marginal notes

What type of notes did King James find offensive? Perhaps the note on Titus 3:1 may serve as an example: “Put them in remembrance that they be subject to the Principalities & Powers, & that they be obedient, & readie to every good work.”

The marginal note in the Geneva Bible stated, “Although ye rulers be infideles, yet we are bounde to obey them in civil policies, and where thei command us nothing against ye worde of God.”

In other words, the marginal note commended disobedience to the king if he issued a command contrary to the word of God. Furthermore, the marginal explanatory notes often attacked the “Papistes” – the leadership of the Catholic Church.

For example, the Geneva Bible translated Revelation 17:4 as follows: “And the woman was arrayed in purple and skarlat, and guilded with golde, and precious stones, and pearles, and had a cup of gold in her and, ful of abominations, and filthiness of her fornication.”

The marginal note on this verse comments: “This woman is the Antichrist, that is, the Pope with ye whole body of his filthie creatures, whose beautie onely standeth in outward pompe and impudencie and craft like a strumpet” [a female prostitute.]

Beloved phrases

Like all Bibles from the period and the later King James Bible, the Geneva Bible contained the Apocrypha — Jewish literature written in the second to first century B.C. but not recognized as Scripture by Jews in the days of Jesus between the Old and New Testaments.

According to “The Cambridge History of the Bible,” the Geneva Bible also used terms that would become common in subsequent English translations, such as “smote them hip and thigh,” “a little leaven leaveneth the whole lump” and “cloud of witnesses.”

The Geneva Bible was a popular Bible for several generations. Even after the publication of the Authorized Version of King James, the Geneva Bible was the more popular translation among Christians who did not belong to the Church of England under the headship of King James.

See more images from the Geneva Bible at the links below:

- Internet Archive has an online copy of the Geneva Bible, 1560.

- British Library has digitized five images of the Geneva Bible, 1570.

- Newberry Digital Collections includes two images of the Geneva Bible, 1599.

- Google Images has a selection of photos of Geneva Bibles .

Mark Rathel, Ph.D., is professor of theology and philosophy at Baptist College of Florida in Graceville, Florida. He enjoys reading and writing about the history of Bible translations.

Mark Rathel, Ph.D., is professor of theology and philosophy at Baptist College of Florida in Graceville, Florida. He enjoys reading and writing about the history of Bible translations.

Share with others: