In our survey of things Jesus did during the last week of His historical life on earth we have seen that on Palm Sunday He entered Jerusalem and was received as a king, and on Monday He drove merchants out of the temple. We come now to two of the busiest days in Jesus’ teaching ministry.

Tuesday and Wednesday

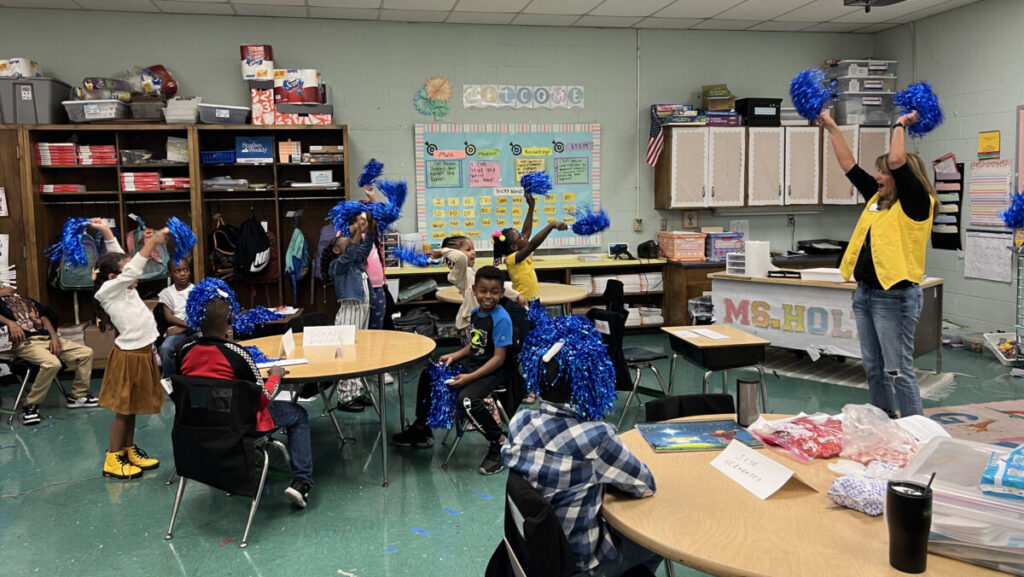

Rob Futral, the author of the Adult Learner Guide for this year’s January Bible Study, lists 14 things that Jesus spoke about on Tuesday and Wednesday. All these are recorded in the Gospel of Luke, and several others are described in the other Gospels, including Jesus’ epochal teaching about the greatest commandment in Torah (see Matt. 22:34–40).

Since Jesus had driven the merchants out of the temple on Monday, it is not surprising that on Tuesday one of the issues was Jesus’ authority. In effect His critics asked Him, “Who made you the judge of what’s going on in the temple?” (see Luke 20:1ff). They were trying to trick Jesus into either saying He had that authority because He was the Messiah, which could be used to incriminate Him with the Romans, or else declining to say He was Messiah, which would discredit Him with those followers who on Palm Sunday had welcomed Him as the Messianic King. Since the question was insincere, Jesus evaded it.

Then He told one of His famous parables. It was the story of a landlord whose tenants refused to give him his share of the grapes and wine that were produced in his vineyard.

Many modern interpreters of Jesus’ parables follow a principle which says that each parable makes a single point, but this one reads like an allegory. The vineyard is Israel (see Isa. 5:1ff), the owner is God, the tenants are the religious leaders of Israel and the servants who come to collect the produce are the prophets. The owner’s son is Jesus, the Son of God, and He is killed in the service of God. With this parable Jesus effectively responded to the question about His authority, and in a way that could not be used against Him.

This parable calls us today to appreciate the unique relationship that Jesus has with God. John expressed this by saying that Jesus is the monogenes (unique, only-begotten) Son of God (John 1:13–14), and Paul expressed it by saying Jesus is the prototokos (firstborn) Son of God (Rom. 8:29).

Here we must be careful. We need to confess that Jesus is God’s unique Son, but confessing it is not enough. The parable makes it clear we also must give to Jesus what we owe to God. We know what that is. Everything.

Jesus’ critics then tried again to trick Him (see Luke 20:20–26). Using flattering words they asked Him whether it was right for Jews to pay taxes to the Roman emperor, who at that time was Tiberius. If Jesus answered no, His critics could tell the Romans that Jesus was a revolutionary, and if He answered yes, His followers would be displeased — people back then didn’t like taxes any more than people today do. Jews especially hated having to pay taxes to pagan Rome.

Once again Jesus foiled His critics’ efforts. Drawing on the fact that the image on the coins was the emperor’s, He said: “Give to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s” (Luke 20:25). That silenced the critics.

Jesus’ words have become a slogan for the principle of religious liberty. Baptists have played an important role in achieving religious liberty. The members of the first Baptist church were English citizens who were living in the Netherlands in order to avoid persecution at the hands of King James. The layman who led these first Baptists back to London was Thomas Helwys, and he wrote a book titled “The Mystery of Iniquity” in which he argued for religious liberty. Helwys sent a copy of his book to King James, after which the king put him in Newgate Prison in London. Within four years Helwys had died, a martyr for religious liberty. In the flyleaf of the book he sent to King James, Helwys wrote this:

“The king is a mortal man, and not God, [and] therefore has no power over the immortal souls of his subjects, to make laws and ordinances for them, and to set spiritual Lords [bishops] over them. … O King, be not seduced by deceivers to sin so against God whom you ought to obey, nor against your poor subjects who ought and will obey you in all things with body, life, and goods, or else let their lives be taken from the earth. God save the King.”

Helwys certainly believed in rendering to Caesar what is Caesar’s. He even said English citizens must obey the king on pain of death. But he also clearly believed in rendering to God what is God’s, and he called on the king not to interfere with that.

Helwys was one of the first people to realize that the way to provide maximal religious liberty for all the citizens of a religiously diverse society is for the government to remain neutral toward religion. In the words of the First Amendment to the American Constitution, the government should neither establish (support) religion nor prohibit its free exercise.

Jesus’ teaching that we should give to government what belongs to government and to God what belongs to God didn’t logically entail all this, of course, but the separation of church and state is an appropriate way to expand Jesus’ teaching.

Moreover it has proven to be a hugely successful social policy. American society, though exceedingly diverse, is nevertheless reasonably united without the glue of an official church to hold it together, and the American people are, without government support, the most religious people in the industrially developed world (Ireland is second and Italy is third). The American vision of religious liberty is now affirmed if not always practiced by almost every nation in the world.

Throughout the remainder of Tuesday and Wednesday, Jesus continued to speak — about resurrection, about David’s son, about the scribes, about the end of the temple and the end of the world and about several other topics.

In the midst of all these weighty topics there is a charming little story. In the temple Jesus and His disciples observed people giving money to support the work of the temple. Jesus was unimpressed by wealthy people who ostentatiously gave large sums of money, but He commended a widow who despite her poverty contributed a small amount (see Luke 21:1–4). He expressed His praise as a paradox: “This poor widow put in more than all of them.” In the Broadman Bible Commentary my friend Malcolm Tolbert wrote of the widow: “Her gift was a genuine expression of her faith that God in His providence would supply her future needs. The rich had shown no such faith. They had not forfeited any of their financial security.”

By Wednesday afternoon Jesus and His disciples must have been exhausted. They went out to Bethany for some much-needed rest.

Share with others: