Jails are now default mental health system because of lack of treatment programs

Think everyone behind bars deserves to be there? Let this statistic sink in: There are now three times more mentally ill people in jails and prisons than in hospitals.

“America’s jails and prisons have become our new mental hospitals,” researchers asserted in a 2010 report issued by the National Sheriffs’ Association and the Treatment Advocacy Center, a national nonprofit organization dedicated to eliminating barriers to the timely and effective treatment of severe mental illness.

Mentally ill prisoners are, according to the report, more likely to:

- Reoffend and recidivate

- Cost more to incarcerate

- Have longer sentences

- Be more difficult for correctional staff to manage

- Commit suicide

- Suffer abuse

Alarming numbers

More than half of all prison and jail inmates are mentally ill, with local jails bearing the brunt of the problem.

The U.S. Department of Justice reported in 2006 that 45 percent of federal prisoners, 56 percent of state prisoners and 64 percent of local jail inmates were found to have a mental health problem.

Female inmates are more likely to be mentally ill than the general population: 61 percent in federal prisons, 73 percent in state prisons and 75 percent in local jails.

The problem is arguably worse in Alabama, whose state prison system is mired in federal lawsuits and operating under a federal court order to fix “horrendously inadequate” prison psychiatric care in state institutions.

In a 302-page opinion issued in 2017, U.S. District Judge Myron Thompson ruled that conditions for mentally ill state prisoners in Alabama were unconstitutional.

In his ruling, Thompson referred to a mentally ill inmate who hanged himself just weeks after providing testimony in the case.

“The case of Jamie Wallace is powerful evidence of the real, concrete and terribly permanent harms that woefully inadequate

mental-health care inflicts on mentally ill prisoners in Alabama,” Thompson wrote.

The Treatment Advocacy Center gave Alabama a grade of D (no state received an A) for its treatment of mentally ill state prisoners, noting that the prison system had only 115 designated forensic (court-ordered) beds, and conducted mental health treatment at only one site in the entire state, the 144-bed Taylor Hardin Secure Medical Facility in Tuscaloosa.

That same year the annual report of the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) reported that 75–80 percent of its more than 21,000 inmates in custody had a substance abuse problem.

While ADOC didn’t specify how many mentally ill inmates it incarcerated statistics show that substance abuse and mental illness are often co-occurring conditions. ADOC boasted in 2017 that it had implemented “the largest substance abuse program within the State of Alabama,” citing 5,183 participants.

That’s still less than a third of the total number of inmates the system says are substance abusers.

While the Alabama Department of Corrections garners most of the headlines it’s important to remember that state prisons are just one slice of the correctional pie.

The U.S. Department of Justice reports a total 40,900 behind bars in Alabama state and federal prisons or local jails and another 60,700 on probation or parole.

That means that of the nearly 100,000 people under some form of correctional control in Alabama more than half are mentally ill, and more than three-quarters are substance abusers.

Lack of programs

When they complete their sentences and are released, typically within one to five years, they are likely to find even fewer treatment resources available to them in the free world.

The dearth of community-based mental health services has been decades in the making.

In the early 1900s, social reformers were shocked at the treatment of the mentally ill who were warehoused in jails and prisons.

A movement launched by famous psychiatric reformer Dorothea Dix led to a generally accepted understanding that the mentally ill should be treated not punished and many new state mental hospitals subsequently were built.

A move to deinstitutionalize mental patients in the 1960s and 1970s, however, resulted in the closing of many mental hospitals.

The community-based services that were supposed to take the place of those institutions never really materialized, and mental health funding has continued to contract.

No place else to go

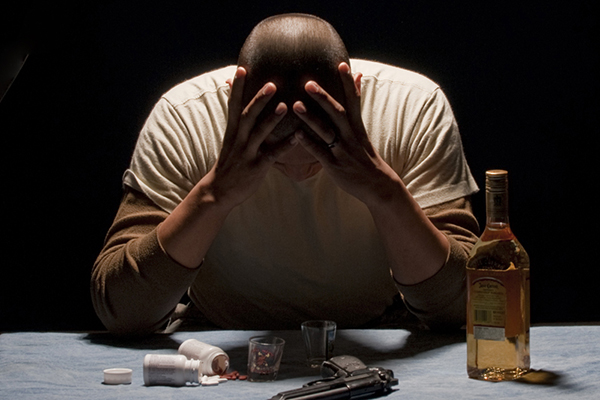

As a result prisons and jails became de facto mental institutions as there is often no place else to hold people who are a danger to the community or themselves.

“In historical terms, we have returned to the early 19th century, when mentally ill persons filled our jails and prisons,” Treatment Advocacy Center researchers reported.

“In 1955 there was one psychiatric bed for every 300 Americans. In 2005 there was one psychiatric bed for every 3,000 Americans,” researchers said.

They also noted that most of the modern-day psychiatric beds are designated only for court-ordered patients.

In its 2016 book “People with Mental Illness in the Criminal Justice System: Answering a Cry for Help,” the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry called for compassionate change and advocacy for the mentally ill.

“There is something terribly wrong with a society,” the book’s authors wrote, “that is willing to spend more money to incarcerate people with mental illnesses than to treat them.”

_____________________________________________________________________________

Local jails have few resources to help inmates who are mentally ill or addicted

If the Mayberry jail were a modern-day reality Otis would probably be bipolar and drug-addicted, sharing a cell with three other mentally ill substance abusers, and Sheriff Andy would be asking the town council for money for more personnel and jail cells.

In real life, local jails largely serve as warehouses for the mentally ill and addicted, the last resort for communities that have no place else for them and insufficient resources to treat them or to help their families cope.

While more than half of all prisoners in U.S. correctional institutions suffer from mental illness, the problem is much worse in the nation’s local jails, where 64 percent of the inmates are mentally ill.

Much worse in Alabama

That problem is compounded in Alabama, according to a survey published by the American Jail Association, because “Alabama has virtually no jail diversion programs and is among the states spending the least on public psychiatric treatment programs.”

As an example of the problems faced by local law enforcement officials, researchers highlighted Tuscaloosa County: “In the Tuscaloosa County Jail, 40 percent of the inmates ‘receive some form of psychiatric care.’ The county sheriff stated ‘the jail is the worst place for someone with a mental illness. … The problem is someone [with mental illness] gets off their meds and a family member doesn’t know what to do, so they call the sheriff’s office. The [person] may end up in jail for 30 to 60 days or even six months for a $300 misdemeanor most people would get out on in a day.’”

Addiction compounds the problem. A 2002 study cited by the American Jail Association showed that three-fourths of mentally ill jail inmates were either addicted to or abused alcohol or drugs, compared with half of inmates who had no mental health problems.

Such studies and statistics ring true for Baldwin County Sheriff Huey “Hoss” Mack, who has served as the county’s chief law enforcement officer since 2007.

“The Baldwin County Sheriff’s Office has definitely seen an increase in the number of individuals who come to us with drug issues and mental health issues,” Mack said.

Greatest impact

“It’s hard to say how many of them are actually addicted, but I can say that a majority of them are at least users coming in. Right now our numbers appear to be somewhere around the 65 to 70 percent mark of those that come to us having drug or substance abuse issues. Meth and opiates are the number one drugs that we are combatting.

“We have also seen an increase in those individuals coming to us in mental crisis and are suffering from drug-induced mental illness. This is typically manifested in the form of paranoia as well as depression,” Mack said.

Incarceration of the mentally ill carries a high price tag.

“We have had to expand our medical services and increase the amount of mental health observations that we offer in the corrections center over the past couple years,” the sheriff said.

“One of the greatest areas that impacts us is the cost of various medications, as well as any counseling we may have to do within the facility. We currently work with the Baldwin County Drug Court, Baldwin County Mental Health and AltaPointe Health’s hospital in addressing these issues,” Mack said.

Many of the Baldwin County inmates are awaiting trial while those who have been convicted of less serious crimes are serving sentences of anywhere from a few days to less than one year.

Baldwin County Jail also houses prisoners convicted of more serious crimes who await transfer to state or federal institutions.

With all that churning of the jail population it takes a lot of manpower and flexibility to address the mental health and substance problems among the inmates.

“Our medical unit — which is staffed by registered nurses and licensed practical nurses along with physicians — may have upwards of 200 medical calls or observations a day,” Mack said. “Our numbers have also increased with working with the probate court on involuntary commitments which usually result in a 72-hour observation and evaluation before those individuals are released on medication.”

No changes in sight

Sheriff Mack doesn’t expect such challenges to change any time soon.

“The lack of treatment facilities is definitely contributing to the revolving door of acute mental illness,” he said.

“Until the state builds, or allows to be built, long-term in-house mental health facilities that will be able to treat these individuals, I am not optimistic of any lasting, positive change.”

Share with others: