When it came to celebrating Christmas, leaders of the 16th century Protestant Reformation were divided on whether followers of Jesus should say “bah humbug” or “joy to the world.”

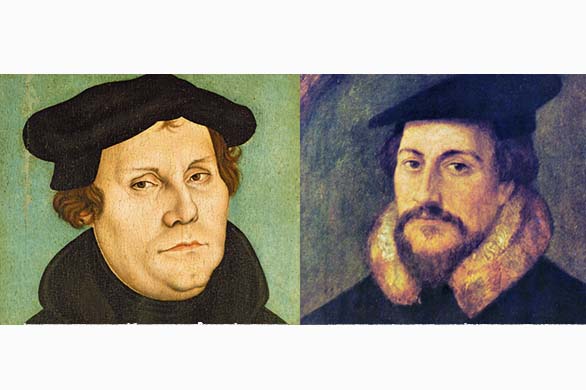

While Martin Luther loved to celebrate Christmas with feasting and special church services, the so-called Reformed wing of the Reformation, led by Ulrich Zwingli and John Calvin, raised objections to such festivities, arguing believers should worship God only in ways explicitly commanded by Scripture and that a festival in December commemorating Christ’s birth was not commanded.

The Reformed wing’s Puritan heirs in England and New England were adamant in their rejection of Christmas celebrations. English Puritan William Prynne (1600–1669) argued, for example, that “all pious Christians” should “eternally abominate” Christmas festivities, said church historian Michael Haykin. In New England celebrating Christmas could result in a fine.

Drawing insight

Though few modern Christians share such sentiments against Christmas, a North Carolina pastor who holds a doctorate in church history said believers can draw insights from both sides in the debate.

Andy Davis, pastor of First Baptist Church, Durham, North Carolina, advocates a “mediating position,” in which believers acknowledge the food and fun of Christmas as good gifts from the Lord but also recognize that secular Christmas festivities can stray far afield from celebrating the incarnation.

“Take the Christmas blessings and look upward to the Giver,” Davis said. “The happiness that we feel when we look at the lights and we enjoy the holiday — all of it comes from God. And ultimately God has so much more to give you than just that. He has His own Son, and the center of everything is the giving of Christ.”

Among the Reformers, differing views of Christmas stemmed largely from differing views of worship, said Haykin, professor of church history and biblical spirituality at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky.

Luther held the “normative principle” — the belief Christians may worship God in any way not forbidden by Scripture — while Zwingli and Calvin held the “regulative principle” — the belief Christians may only worship God in ways commanded by Scripture.

Thus, Luther retained the Roman Catholic traditions of Advent and Christmas and may have been among the first people to decorate a Christmas tree with candles, Haykin said. “It was a festival he delighted to celebrate.”

The first seven sermons in “The Complete Sermons of Martin Luther” edited by John Nicholas Lenker are all designated for the Christmas season.

For Zwingli and Calvin, in contrast, “there are questions raised about” Christmas, Haykin said. He noted all Reformers praised God for the incarnation but differed over the appropriateness of an official festival Dec. 25.

Elevating one day

Preaching on Christmas Day 1551, Calvin noted, “I see here today more people than I am accustomed to having at the sermon,” according to Calvin’s “Sermons on the Book of Micah” translated by Benjamin Wirt Farley.

Then Calvin warned, “When you elevate one day alone for the purpose of worshipping God, you have just turned it into an idol. True, you insist that you have done so for the honor of God, but it is more for the honor of the devil.”

Being cautious

Still, Calvin’s admonition seemed to be a caution rather than a prohibition of Christmas.

In a 1551 letter quoted by Presbyterian pastor Phil Larson, Calvin said he “pursued the moderate course in keeping Christ’s birthday.” Similarly, in a 1555 letter he noted, “A church is not to be despised or condemned because it observes more festival days than the others.”

Nearly a century later the Puritans, who drew theological inspiration from Calvin among other sources, took his view a step further, formally outlawing Christmas in England in 1647, Haykin said.

In America the Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony permitted nonbelievers among them to celebrate Christmas in the early 1620s, Davis said. But when some nonbelievers were seen playing a game on Christmas Day, the colony’s governor “confiscated their game equipment and said they were free to not work, but they had to stay indoors and would best spend the time by reading the Bible and praying.”

Caution about Christmas in British territories prevailed until the 1800s, Davis said, because of a desire not to return to Roman Catholic practices.

The Reformers’ and Puritans’ reticence about Christmas should not be dismissed altogether in the modern world, Davis said, noting the holiday often is celebrated with “fantastic busyness” and “materialism” but “no real, vibrant piety.”

Even when charity and thankfulness are involved in the celebration, Davis said, meaningful references to Christ can be removed, as in Charles Dickens’ famous novella “A Christmas Carol.”

Yet “you can go too far in the opposite direction” by eschewing traditional Christmas celebrations altogether, Davis said.

“The ‘eat, drink and be merry’ thing is like scraps that fall from the table of God. It’s common grace blessings that people enjoy,” he said. “Why wouldn’t you want something like that?”

Following the culture

It’s understandable that some Christians reject Christmas activities that are merely cultural with no celebration of Christ, Davis said. But the culture “just doesn’t get it” when Christians denounce the holiday altogether.

A more productive message in 21st century America is, he said, “These blessings are gifts from God. But He has so much more to give you than that. He came into the world to save sinners.” (BP)

Share with others: