A teenage boy who is afraid his athletic abilities won’t measure up to his parents’ expectations. A suburban mother who wants the energy to keep up with her family’s hectic schedule. A truck driver who needs to stay awake for a long haul. A young beauty queen who wants to stay thin.

Though these individuals come from different ages and stages of life, they all have something in common — they are addicted to methamphetamine.

In his State of the State address in January 2006, Gov. Bob Riley called methamphetamine “Alabama’s No. 1 illegal-drug threat.”

In a 2005 survey of county law- enforcement agencies in 45 states conducted by the National Association of Counties, 58 percent of officials reported that methamphetamine, or meth, is the primary drug problem in their county.

In the same survey, 70 percent of officials reported an increase in robberies, 62 percent an increase in domestic violence and 53 percent an increase in simple assaults due to meth abuse. Twenty-seven percent also reported an increase in identity thefts attributed to meth.

According to the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, nearly 12 million Americans aged 12 and older have tried methamphetamine, representing 4.9 percent of that population segment. Results from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse show that in 2000, there were 344,000 new users of methamphetamine, aged 12 to 25, with the average age of new users at 18.4 years.

On the street, methamphetamine is known as “speed,” “tweak,” “ice,” “crank,” “chalk,” “crystal” or “crystal meth.”

The white, odorless, bitter-tasting crystalline powder can easily be dissolved in water or alcohol, and the drug can be ingested, inhaled, smoked or injected.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, a methamphetamine high can last six to eight hours, and users experience an initial “rush” followed by a state of high agitation that can lead to violent behavior.

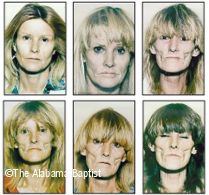

The short-term effects of meth use can include euphoria, increased attention and activity and decreased fatigue and appetite. The long-term effects are similar to those of other drug addictions. Paranoia, hallucinations, mood disturbances, extreme weight loss and even stroke also can occur.

First produced in Germany in 1887, amphetamines have been used to treat everything from depression to congestion. Methamphetamine — a more potent derivative of amphetamine — was developed in Japan in 1919, and both amphetamines and methamphetamines were widely used by soldiers and factory workers during World War II to help them stay alert.

In the 1950s, physicians commonly wrote prescriptions for amphetamines as a treatment for weight loss and depression, and both amphetamines and methamphetamine were widely available on the street market.

The drugs often were used by college students, truck drivers and athletes to improve alertness and stamina and were known as “Bennies” or “speed.”

The illegal use of methamphetamine decreased with the passage of the 1970 Controlled Substances Act, which restricted the legal production of amphetamines. At the same time, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and medical licensing boards cracked down on doctors who freely wrote amphetamine prescriptions. The abuse of the drug, however, has been on the rise since the mid-1990s.

“Meth has been around forever, but what’s changed is the extent to which the population is affected,” said Gregory Borland, assistant special agent in charge of Alabama for the DEA.

A synthetic adrenaline, amphetamine is produced in the lab like other legal medications. Illegal use of meth increased when a process was discovered that allowed people to extract the main ingredient, ephedrine, from pseudoephedrine — a common chemical used in over-the-counter sinus and allergy medications — thereby allowing them to make their own illegal meth.

This led to an epidemic of home labs — known by the DEA as small toxic labs, or STLs — where small-time cookers could make meth to use and sell.

“The need for specialized chemicals [to make methamphetamine] was eliminated, and we started to see more prevalence of these small toxic labs,” Borland said.

Phillip Drane, executive director of The Shoulder, a private, nonprofit, Christian drug and alcohol treatment center in Daphne, said that one of the most unfortunate things about meth is the easy availability of the recipe for “cooking” the drug.

“You can go to any major bookstore or go online and buy recipes and books that tell you specifically how to cook meth,” he said.

Alabama’s rural areas have seen the brunt of the methamphetamine epidemic for two primary reasons, Borland said.

“Meth labs require open spaces to avoid detection because of the odors that are given off,” he said. “Also the drug itself has long been used mainly by working people — particularly rural white people — who use the drug so they can squeeze more hours out of the day.”

The number of methamphetamine labs in Alabama increased dramatically between 2001 and 2004, according to Borland. From Oct. 1, 2001, through Sept. 30, 2002, 355 labs statewide were discovered and closed. In 2003, the number increased to 397 and to 523 in 2004.

Last year’s numbers dropped to 418 labs, Borland noted. He credited the decrease to a new state law, which went into effect in 2005, that limits the amounts of pseudoephedrine-containing products that can be sold to an individual. The law also requires that these products be locked up or stored behind a counter or barrier accessible only by retail employees. Customers are also required to show a valid ID and sign a logbook. The effect of the law was immediate, Borland said.

“This law had a chilling effect on people who went into stores and bought large quantities of these medications,” he said. “During the period of July 1 to Dec. 31, 2004, the DEA paid for the cleanup of 381 methamphetamine labs in Alabama. During the same period in 2005, there were only 95 labs cleaned up. That represents a decrease of 75 percent, which is amazing.”

Borland warns, however, that these numbers could also be misleading.

“These numbers are good news, but we don’t want to create the false impression that [the methamphetamine problem] is under control,” he said.

Since neighboring states enacted similar laws regulating the sale of products containing pseudoephedrine, it has become more difficult for small-time labs to get the ingredients.

But though small operations are closing, “at the same time, we’re seeing an influx of Mexican drug-trafficking operations bringing meth into Alabama in huge quantities and in a much more pure form,” Borland said.

“That the number of labs is down is great news … ,” he said. “But it shouldn’t be interpreted that the meth threat is abating.”

Share with others: