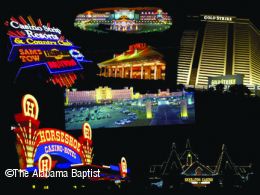

The dazzling lights of nine casinos flood miles of farmland in the Mississippi Delta, blasting across the region as if they had more to compete with than a few catfish ponds and cotton fields.

Nothing hinders the casinos’ glow in the flat expanse of Tunica County, Miss. For the poverty-stricken area, the lustrous resort complex is the moon that rises every night in the west, glimmering in the Mississippi River on one side and penetrating the shadows of pawnshops on the other.

The area’s financial and political tide has ebbed and flowed to the gaming industry’s dominion for nearly 20 years now. Many tout it as a good thing for the county and the state. Who even questions it anymore or for that matter, even notices?

Adam does. He does despite the fact that it barely noticed him that summer. A 19-year-old college student, Adam looked for a summer job in the employment-starved Delta and found it in the booming Tunica Resorts area — now the nation’s third-largest gambling region behind Las Vegas and Atlantic City, N.J.

"I thought $10 or $11 an hour was pretty good for a summer job," he said. But all the money in Tunica couldn’t counter the horrors Adam experienced working for a casino.

His employers suited him up and assigned him to the "heartbreak" shift, running the shuttle bus back and forth to the parking lot from midnight ’til 8 a.m. each day.

"My first night, I picked a gentlemen up in the parking lot right when I first got there. I dropped him off at the door. He told me he drove an 18-wheeler for a living. At 5 a.m., he came out bawling his eyes out. In five hours, he had given them everything he had — he even gave them his house," Adam said. "The casinos are prepared to take anything from you — they have ATMs, they’ll cash your paychecks, they’ll take your property."

That was only the beginning. For weeks, no one came out happy from the bowels of the casino in the wee morning hours — "not unless they were drunk," he said.

One man punched the side of Adam’s bus. Another plowed his truck into an embankment. And fights took place constantly.

"I saw a guy beating his wife in the parking lot one night and had to call the sheriff’s department," Adam said. "All kinds of crazy stuff happened every night."

But the worst was still to come.

One morning around 4:30, he was driving a larger casino bus down U.S. Highway 61, the main route into the area, when an 18-wheeler passed him. Seconds later, the truck slammed on its brakes in front of him.

"When I eased up to go around him, I saw that there was a person laying on the white line by the truck — it was barely even a person," Adam said. "He had walked out in front of the 18-wheeler. He could’ve just as easily walked out in front of my bus."

The next day, as Adam was picking people up, a woman told him the man was one of her relatives. He had lost everything at the casino and while he was walking home, decided to end it all.

For weeks, Adam was shaken. He spent his time behind the wheel with the wheels turning in his mind, examining from every angle the business that provided his paycheck but garnered that of so many others.

"The casinos make a bunch of promises when they come in, that they’re going to build up schools and the community. But they are generating those funds off the backs of the people in the area," Adam said. "They can’t pay the bills by giving out money, but every now and then, someone would win a little. They give a little bit out just to keep people thinking they can win."

And even then, many times, the casinos get it back, he said.

Adam remembers one woman who won about $10 million that summer. The casino put her face on a billboard as a big winner and sent her home in a limo. She told reporters she planned to buy a house for her mother, who had never owned a home.

The casino offered the woman a nice place for herself, too — a high-roller suite on the premises and a limo ride to the casino whenever she wanted it.

"She never bought that house for her mom. In six months, she lost it all," Adam said.

He was not really surprised. "My major was psychology and we studied once what happens when rats have to push a button for food. If they know that every time they push it they’ll get food, they only get what they need. If it happens every third time, they will push it ’til they learn the pattern; then they will only get what they need. But if the pattern is random and they don’t know when they will get something, they keep doing it and doing it and never stop."

Same with humans, Adam said. In the casinos, walls without windows or clocks hold in gamblers who have no concept of time as hours and even days pass. They waste their lives and livelihood away, he explained.

"The casino says it’s the person’s fault if they don’t have enough willpower to just eat a nice, affordable dinner; spend a little at the slots; and stop, but they play to people’s weakness. It’s intrinsic in all of us."

And a summer of watching it was more than plenty for Adam. That summer started a string of events that eventually led to a recommitment of his life to Christ and a call to the ministry. "I saw a lot and I learned a lot. But I would never go back and do that over. Too many things happen there — and too many people hurt as a result."

EDITOR’S NOTE — Name has been changed.

Share with others: