EDITOR’S NOTE — February is Black History Month.

Charles Octavius Boothe (1845-1924) was an Alabama Baptist preacher, educator, author and determined advocate for African American advancement.

Born into slavery on June 13, 1845, in Mobile County, Boothe was the slave of planter Nathan Howard Sr. Some accounts say that teachers who boarded at Howard’s house taught Boothe to read. Other accounts say that Boothe taught himself the alphabet from the lettering on tin pie plates. At the age of six after his first owner died, he went to live with owner Nathan Howard Jr.

Boothe learned to read the Bible and was raised in the Baptist church. He experienced a conversion after the Civil War. Baptized in 1866, he was ordained as a minister in 1868. Boothe was strongly involved in teaching basic literacy, as well as religious and moral education, to African Americans.

He helped establish the Colored Baptist Missionary Convention of the State of Alabama in the early 1870s, which served as a ministerial alliance of Black Baptist churches. The organization devoted its energies to evangelizing, improving the African American race, and participating in ministerial training. Boothe served as recording secretary and as a missionary, preaching to freed slaves.

He established and pastored two churches after the Civil War. He started the First Colored Baptist Church in Meridian, Mississippi. Then in 1877, he helped found the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery and served as its first pastor. The church became famous during the civil rights movement because of its pastor, Martin Luther King Jr. The church’s name was changed to the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church in 1978.

Educator and writer

Boothe was one of the founders of Selma University in 1878 and served as an early president. A prolific writer, Boothe was editor of a religious newspaper, the Baptist Pioneer, writing newspaper articles and reports on missionary activities. He used subscriptions to underwrite some of the university’s expenses.

Boothe also wrote two books. His first one, “Plain Theology for Plain People” (1890), communicated Christian doctrines in an understandable way for Black Baptist ministers and their church members. He explained the doctrines of God, salvation, Christ and the Bible from a distinctly Baptist and moderately Calvinist perspective. In 1895, he wrote “The Cyclopedia of the Colored Baptists of Alabama,” which recorded the works of African American Baptists in Alabama.

Boothe traveled regularly throughout central Alabama from the early 1870s until 1900. He conducted ministerial training institutes on basic literacy and elementary Baptist beliefs, as well as more advanced theological concepts. He strongly urged church leaders to hold members accountable for living a moral life. He hoped that righteous, biblically articulate church members would put a stop to the racist beliefs among many white people that without slavery African Americans would become uncivilized.

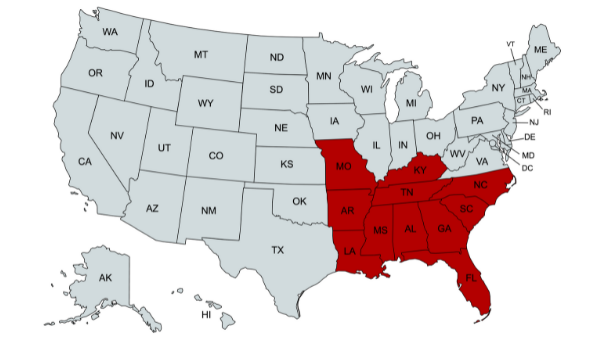

He worked with other Baptist groups to obtain funding for missionary efforts and educational institutions. Support came from major organizations such as the Alabama Baptist State Convention to help fund his ministerial institutes and to help ill-prepared African American preachers. He later received support from the Southern Baptist Convention to assist African Americans who were migrating to northern cities.

Boothe worked tirelessly for 50 years, striving to improve the condition of African Americans and at the same time working against racial oppression. He moved to the North sometime in the first decade of the 20th century. Little is known about him after he left Alabama. He died in Detroit in 1924.

No longer ‘unknown theologian’

Boothe has sometimes been called the “Unknown Theologian.” No longer. In 2017, his “Plain Theology for Plain People” was reprinted by Lexham Press at the urging of Walter Strickland, associate vice president for diversity and assistant professor of systematic and contextual theology at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Wake Forest, North Carolina.

Strickland, who rediscovered the book, told Baptist Press in 2018, “Boothe’s work is important today because it positions black evangelicals in the broad spectrum of the evangelical tradition.” He went on to say that Boothe’s book explained “the doctrines of our holy religion” with “simplicity of arrangement and simplicity of language.”

Click here to read more about Boothe’s life and writings.

Share with others: