Bible Studies for Life

Assistant Professor of Religion, Samford University

Confront Sin

Daniel 5:17–28

While the Neo-Babylonian empire was at one time unmatched in its exercise of power, its rule was not meant to last. Less than a century would pass between the founding of the empire in 626 B.C. by Nebuchadnezzar’s father and its collapse in 539 B.C. One of the factors that led to this early collapse was the disastrous reign of Babylon’s last king, Nabonidus.

From time immemorial, Babylon had held its patron deity to be the god Marduk (Jer. 50:2). The new Babylonian king had different theological ideas, however. Nabonidus was not a member of Nebuchadnezzar’s family but was instead a usurper who traced his roots to the Aramean town of Haran. In Haran it was the moon god, Sin (pronounced “Seen”), who was the chief god. Influenced by his ancestral traditions, Nabonidus removed Marduk from his place at the head of the pantheon and installed Sin instead. This move scandalized the priests of Marduk and alienated the king from his Babylonian subjects. The crisis became so bad that the king actually had to leave his crown prince, Bel-shar-usur, Daniel’s Belshazzar, in charge.

So great was the animosity toward Nabonidus and his family that when the Persians marched on Babylon in 539 B.C., the people welcomed them as liberators and surrendered without a fight. If Isaiah affirms that Persia rose to rescue the Jews, Daniel also notes that Babylon fell because of the arrogance of her rulers.

Point to the consequences of sin. (17–21)

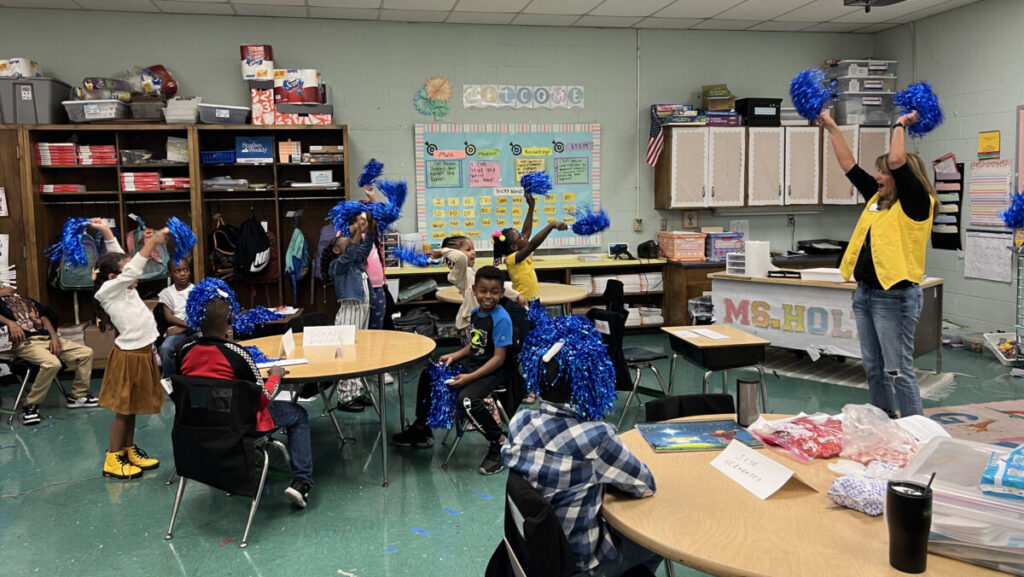

The fifth chapter of Daniel opens with a description of a grand banquet hosted by the Babylonian ruler, Belshazzar. In the midst of the banquet Belshazzar is said to have ordered that the sacred vessels from the temple in Jerusalem be brought for the guests to use for the feast. One can only imagine that this must have been a bit of “adding insult to injury,” taking what were sacred items to the Jews and reminders of the now-ruined temple and using them for some royal party. No sooner had the vessels been passed around that then a hand appeared announcing Belshazzar’s doom.

Be specific. (22–23)

The words that formed the cryptic handwriting on the wall were “mene, mene, tekel, parsin.” Individually the words were easily understood. Each is an Aramaic term referring to a measurement of weight, but the larger message of the words was a complete mystery.

When his sages could not divine the meaning of the writing, Belshazzar finally followed his queen’s advice and called for Nebuchadnezzar’s old counselor, Daniel, to give its interpretation. With boldness and apparently some contempt, Daniel confronted the king, charging him with having ignored the fate that came upon Nebuchadnezzar when he too had grown prideful. Now Daniel declared it was Belshazzar who had acted arrogantly, treating as common vessels that which were sacred to God.

Make them aware that sin brings judgment. (24–28)

Daniel then explained the message whose meaning had eluded the king’s magicians. While “mene” signified the weight, “mina,” it also stood for the verb “mena,” or “to number.” God had numbered the king’s days and brought them to an end. “Tekel” denoted a shekel but also stood for the verb “tekil,” or “to weigh.” God had weighed the king and found him wanting. “Peres” signified a half-mina but also stood for the verb “peris,” or “to divide.” Belshazzar’s kingdom was divided and given to another. That very night the Babylonian empire and the Babylonian ruler both met their end.

Share with others: