Abruptly the white, Toyota truck turns off Bauchi Highway. For a moment, it stops. With a hand-held Garmin Global Positioning System (GPS), Harriet Bowman picks up latitude-longitude readings from five satellites.

“LEFT THE HIGHWAY,” she prints in her black notebook.

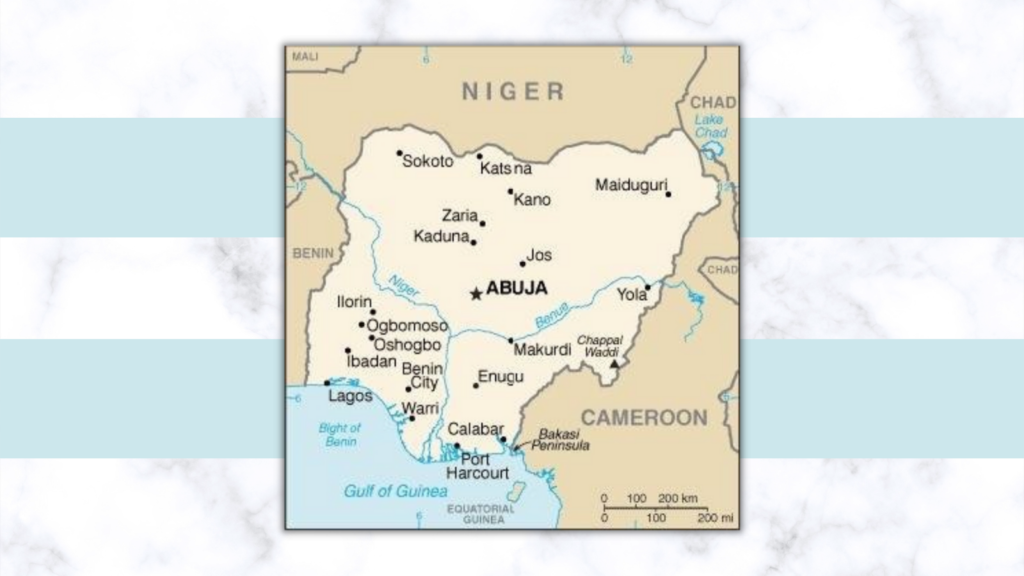

With frequent GPS readings, she and her husband, Clint, will later plot newly discovered villages on a handmade map at home.

Working beside Nigerian Baptists who know various dialects and these uncharted regions, the Bowmans are part of the nine-member engagement team for the International Mission Board (IMB) in West Africa. Their job is to research and locate all the unreached/unengaged people in Nigeria and then initiate strategies for starting work among the nearly 200 groups.

Off-roading missions — Bowman-style — constitutes an extreme adventure in faith.

They may meet with local resistance from Muslim leaders or the practitioners of an African traditional religion called dodo who wear fearsome masks and threaten with canes.

“Some of our Nigerian pastors could get hurt helping us,” Clint Bowman admitted. Often the team includes the Bowmans’ 12-year-old son James.

Rivers flood and mud flies as their truck crawls over trails that have dissolved into a slippery, thick morass during the rainy season. Mud holes can be the worst. Regularly the truck gets stuck.

“I’ve seen Clint’s truck buried so deep in the mud that the front wheels were bowing in,” said Larry Taylor, occasional rescuer and business facilitator for the IMB in Nigeria.

Nearly impassable mud hardens during the dry season into deep and unyielding ruts. Braking and maneuvering through the bush, the Bowmans work hard to control the four-wheel drive.

“Sometimes I just close my eyes and keep going,” Harriet Bowman said with a laugh.

She drives with a frozen shoulder. At best, it is a bone-jarring, rock-and-roll ride.

When branches slap the windshield and poke into the open window on the driver’s side, steering requires quick, sure reflexes. It also requires staying alert to what lies ahead. Shaky wooden bridges here can straddle steep ravines. And in the dry season, villagers may partly or totally dismantle their bridges for firewood.

The attributes that serve the Bowmans as drivers serve them in the assignment as well. With clear focus, they pursue the long-range strategies and yet remain alert to providential twists and turns ahead. As they pray, they have a strong sense God is about to do something big in Africa. One-fourth of all Africans are Nigerians.

“Things could start here and spread,” Harriet Bowman reasoned.

With that idea, they keep pressing ahead.

“Clint is a global thinker,” Taylor said. “He can see need and break it down into chewable chunks. They just make their plans and start to chew away.”

Overall their plan is to find unreached people and encourage others to plant churches as needed. If the team discovers a village has a Christian church, they note it in their black book and move on.

Only with approval from parents, they will witness to teenagers and children. When the team starts a church, they encourage it to reach out to the next village. “We want church planting in its DNA,” Clint Bowman said.

The Bowmans traverse at least three worlds. They are Westerners in Nigeria. When they leave the highway, they embark on bumpy, one-lane roads that turn into dirt bike paths. Once out of the truck, they follow even narrower footpaths winding through tall grasses or through 12-foot-high walls of corn. When they arrive at their destination, they are like science fiction travelers stepping back 2,000 or 3,000 years in time. In this beautiful, agrarian world, men farm with simple hand tools. Over pungent, open fires, women prepare meals. As in the days of the Old Testament’s Moses, clay bricks are handmade from mud mixed with straw. Water is drawn from wells.

Right now, the team’s efforts are divided about evenly between Muslims and followers of traditional African religions.

As Westerners drive along the back roads of northern Nigeria, typically the children wave and exclaim, “‘Biture, biture’ (white people)!” But when the Bowmans’ Toyota truck passes by, more often, the children respond with a wave and a shout: “White people — with black people!”

It’s been that way since the Bowmans first arrived in Nigeria.

“Clint would rather be with Nigerians than a bunch of missionaries!” observed Mike Stonecypher, an IMB liaison with the Nigerian Baptist Convention whose home church if First Baptist Church, Glencoe.

The Nigerians respond to that love almost the moment they meet, said Stonecypher who has accompanied Clint Bowman on a number of bush adventures.

Taylor recalls how one day Clint Bowman’s truck tire slid through a bridge when the lumber shifted.

“God provided three line-backer-sized Nigerians” from a nearby village to help Clint Bowman out. Which way did he go from there? Taylor said, “Clint only goes forward.”

That drive is as evident in all the dots for villages and the tiny red crosses that sprinkle the large, hand-drawn map posted in the Bowmans’ home. When a Muslim leader forbade them from starting a church in one village, Clint Bowman just started new work in the villages surrounding it.

“More and more Southern Baptists are becoming servants as we look for ways to strengthen Nigerian Baptists,” Stonecypher said. “But there is a second role, and that is to take the lead — going to the tough places where the gospel has been resisted or has not been heard. Here the Bowmans are showing the way.” (IMB)

Share with others: