By Martha Simmons

Correspondent, The Alabama Baptist

Contrary to political rhetoric and common public opinion, serious crime in the United States has been declining for years, a trend mirrored in Alabama’s own experience.

A recent Pew Research Center report notes that violent crimes and property crimes have fallen significantly over the past couple of decades. Annual data collected by the FBI, which compiles law enforcement agency data, and the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), which surveys 90,000 households nationwide, indicated these long-term trends:

• Violent crime has fallen sharply from 1993 to 2015 (the latest year available) — by 50 percent according to the FBI’s law enforcement data, and 77 percent according to BJS’s survey data, which includes unreported crimes. FBI did report a 3 percent increase in violent crime between 2014 and 2015.

• Property crime has likewise declined during that period — 48 percent according to the FBI and 69 percent according to BJS.

Alabama’s total serious crimes (including violent and property crimes) during the last couple of decades also have declined, according to the Alabama Criminal Justice Information Center (ACJIC). There were 162,476 serious crimes reported in 2015, compared to 198,356 in 1993.

ACJIC data indicates that much of the progress in reducing the crime rate has been made during the last few years.

“In a Pew Research Center survey in late 2016,” researchers reported, “57 percent of registered voters said crime had gotten worse since 2008, even though BJS and FBI data show that violent and property crime rates declined by double-digit percentages during that span.”

Undeserved reputation

Likewise some cities get an undeserved reputation for high crime during the heat of a campaign. Chicago made headlines in 2016 for its murder rate, despite the fact that its murder rate was less than one-third of the murder rates in St. Louis and Baltimore, according to crime data collected by the FBI.

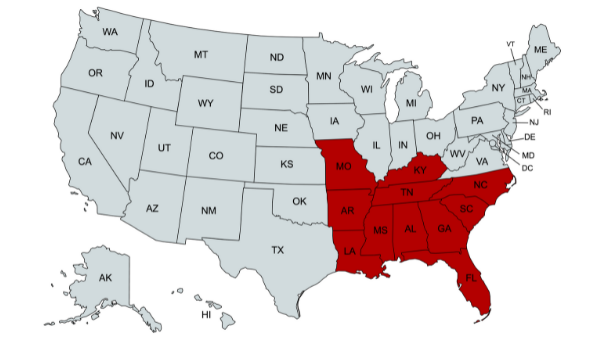

However, crime rates do vary widely from one geographic region to another and can be attributable to factors such as population density and economic conditions. “In 2015 for instance there were more than 600 violent crimes per 100,000 residents in Alaska, Nevada, New Mexico and Tennessee. By contrast, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont and Virginia had rates below 200 violent crimes per 100,000 residents,” Pew reported.

Alabama’s crime rates also vary widely from county to county. For instance the 2015 index crime rate (expressed in serious crimes per 100,000 population) in Jefferson County, the state’s most populous, was more than twice that of comparatively rural and affluent Baldwin County, according to ACJIC.

While it’s encouraging to see crime rates decline overall, it’s important to remember that many crimes are never reported in the first place.

“In 2015, the most recent year available, only about half of the violent crime tracked by BJS (47 percent) was reported to police. And in the much more common category of property crime, only about one-third (35 percent) was reported. The proportion was substantially higher for offenses classified as serious violent crime (55 percent), a category that includes serious domestic violence (61 percent of which was reported), serious violent crime involving injury (59 percent) and serious violent crime involving weapons (56 percent),” Pew researchers wrote.

Pew survey respondents attributed the lack of crime reporting to a variety of factors, including doubts police would help, the feeling it was too trivial a matter to report to police or it was a personal matter they preferred to handle themselves.

Lack of crime reporting

Baldwin County’s two top law enforcement officials weighed in on the issue.

Sheriff Huey “Hoss” Mack said, “Submission to the FBI UCR (Unified Crime Report) is voluntary for most agencies. With that in mind I view the UCR as a true but not complete picture into the criminal activity in a particular area. Most unreported crime falls into the misdemeanor and violation categories. Felony crimes are more reported due to their nature and court actions.”

Baldwin County District Attorney Robert Wilters, who spent more than two decades as a judge and before that was an FBI special agent, said lack of crime reporting can be highly localized and crimes can affect people disproportionately.

“In some neighborhoods, it’s sort of a way of life that at some point in your life, your car will be broken into or stolen. If they don’t have the means to fix the broken window or replace that car, what are they going to do? Some people live on the razor’s edge financially and a small crime that some people might overlook can be a major crime to other people.

“And in some neighborhoods a crime of violence will not be reported to police because it’s sort of an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, that ‘if you hurt one of my people, I’ll hurt one of your people,’” he said.

Both the sheriff and the district attorney believe faith matters when it comes to preventing crime and rehabilitating offenders.

“God wants us to look out after our friends and family and that’s what we should do — pay attention,” Wilters said. “Don’t just go home, close the door and not go outside. Be active in your community. We’ve got to pay attention to what’s going on. That’s a godsend when people are watching out for you.”

Power of prayer

Wilters believes in the power of prayer too. “Pray for our victims of crime, for the offenders, for law enforcement, judges, juries.”

An important part of the drug court he presided over as a judge and remains involved in as a district attorney is connecting offenders with people of faith. Volunteer chaplains are available at drug court to pray with offenders and have private conversations with them. “There’s someone in the courtroom that they can talk to about anything and everything and it’s not going to go any further than the offender, the chaplain and God. That can be a big turning point in someone’s life.

“Too many people in drug court are unchurched or haven’t been in such a long time, they’ve forgotten and they have no hope,” Wilters said. “As a Christian, if I’m going through bad times, I know God’s going to be there with me, He’ll never abandon me. If I’m going through some bad times, I have hope that there will be a better day.

“But if you’ve got no hope for a better life, you continue on that path of destruction. It’s a slow way of committing suicide.”

Prayer and faith and hope are powerful tools, Mack said. “As people of faith, I ask for prayers for our deputies and employees. I also ask for prayers for our inmates. We average a daily count of 525 inmates and we need prayerful support for them while they are incarcerated and physical support when they are released. I personally believe that a person who has faith also has hope. Hope is key to any rehabilitation or change in a person’s life,” Mack said.

“Faith first, which leads to hope, which leads to the promise of something better.”

Share with others: