By Jana Reiss

Religion News Service

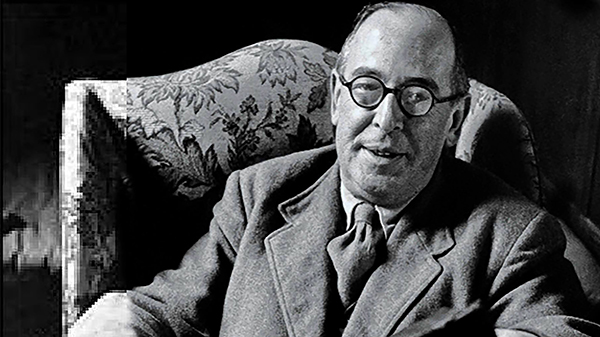

Drawn from his fiction and nonfiction writings, “The Reading Life: The Joy of Seeing New Worlds Through Others’ Eyes” takes snippets of C.S. Lewis’ various writings, all themed around the capacious love he had for books and reading, and gathers them into a gift book perfect for the new year.

Nostalgia for childhood

The pieces are short and well-chosen, and often draw upon nostalgia. Several times in different essays, Lewis reflects on children’s literature as a nourishing source of adult reflection. He says those stories meant something different to him as a mature man than they did in childhood, but that very timelessness is what makes them important to revisit.

“When I became a man I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up,” he writes.

This attraction to myth and children’s fantasy leads him to review his friend J.R.R. Tolkien’s work. Lewis’ early reviews of “The Hobbit” and “The Fellowship of the Ring” are included in the collection and make for fascinating reading for anyone who loves the series.

He urges people to take “The Lord of the Rings” books seriously as literature, asserting readers who revisit “The Hobbit” again and again will realize “what deft scholarship and profound reflection have gone to make everything in it so ripe, so friendly, and in its own way so true.”

“Prediction is dangerous,” Lewis writes, “but ‘The Hobbit’ may well prove a classic.”

In a similar vein, he notes that true readers just don’t have an age-based timetable for what they find interesting:

“The neat sorting-out of books into age-groups … has only a very sketchy relation with the habits of any real readers. Those of us who are blamed when old for reading childish books were blamed when children for reading books too old for us. No reader worth his salt trots along in obedience to a time-table.”

Lewis covers some familiar and controversial questions — is it permissible to dog-ear a book? No, he insists; such behavior ought to fill us with shame. (I stubbornly dog-eared that page.) Yet he gives the thumbs-up to marginalia: He underlines, indexes and comments in his books, particularly ones he didn’t think were very good, thereby making them his own.

“Many an otherwise dull book which I had to read I have enjoyed in this way, with a fine-nibbed pen in my hand: one is making something all the time and [a] book so read acquires the charm of a toy without losing that of a book.”

Not all of the essays are lighthearted love letters to the act of reading. In “The Case for Reading Old Books,” he takes on a question that plagues me constantly: What will turn out to have been the blindnesses of our own age?

When we read writers across the centuries, we are alive to their false assumptions in a way they were not able to be:

“Nothing strikes me more when I read the controversies of past ages than the fact that both sides were usually assuming without question a good deal which we should now absolutely deny. … We can be sure that the characteristic blindness of the 20th century — the blindness about which our posterity will ask, ‘But how could they have thought that?’ — lies where we never would have suspected it, and concerns something about which there is untroubled agreement. …”

‘Magic about the past’

When we read this collection more than half a century after Lewis’ death, his own blind spots will seem obvious to us — his utter lack of attention to questions of gender, race and colonialism; and his assumption that the Western canon of literature is canonical because it is superior and not simply because it helps to reify those assumptions about gender, race and colonialism.

But that’s not the point. Or at least, that’s not the only point. That essay, like all great literature, should make us pause and turn the tables on ourselves, and try to spot our own Achilles’ heels. It’s not that “there is any magic about the past,” as Lewis makes clear. People were not cleverer or more moral then than they are now.

But a regular habit of keeping “the clean breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds,” as Lewis wrote, broadens our perspective and makes us challenge the unquestioned assumptions of our age in a way that reading only contemporary writers cannot.

Share with others: