The Fulani herder grabs a large bull by its sharply pointed horns and then, slipping one thumb in the animal’s mouth, firmly rotates its head to the side and holds it. The sleek, white animal is hobbled, his tail twitching. Yero (not his real name) passes a syringe to veterinarian Mike Houser, who makes the injection and then quickly pops the animal on the rump. The owner adds a red mark to its hide and they move on.

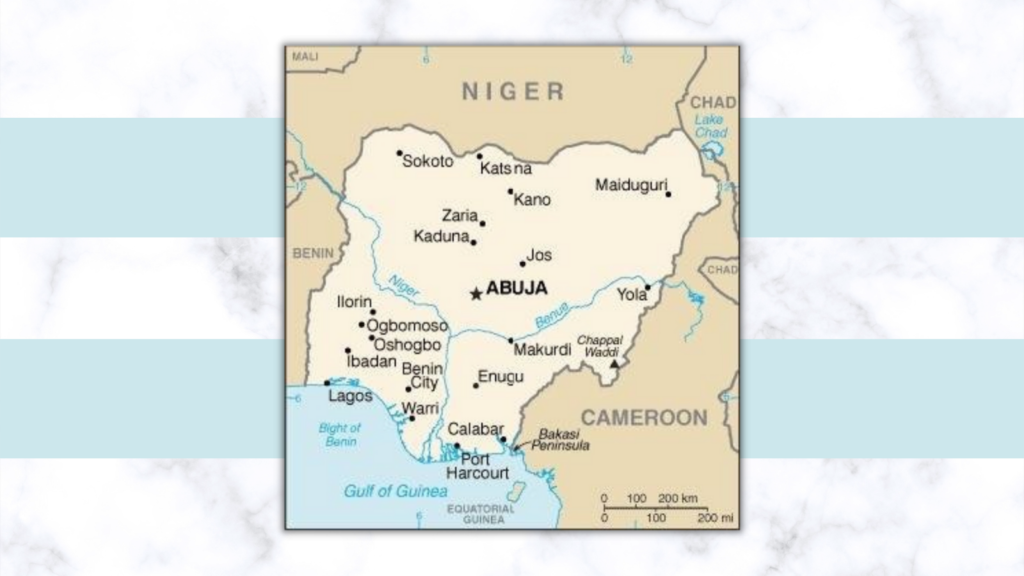

Houser, a missionary with the International Mission Board (IMB), and his ministry partner, Yero, work in Kaduna state, Nigeria, treating animals. The two arrived at 8 a.m. They started with Yero’s quiet prayer of blessing for the owners and their herds. Before noon, they will be finished.

The Fulani address Houser as "doctor."

He and Yero are professionals. So are the owners.

The Fulanis are pastoral nomads, much like the Old Testament patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.

It is not unusual to see a white herd crossing a Nigerian road or rambling through a large pasture — followed by family members, including tall, elegant women balancing cooking pots and bowls on their heads — and one or two animals saddled with small tents.

"My grandfather used to say that the man without cows is a man without clothes," Yero said. "For the Fulani, his cattle are his gold."

At 18 million, the Fulani are the largest nomadic group in the world. Centuries ago, they converted to Islam. At the Fulani Empire’s height through the 1800s, it spread Islam throughout West Africa.

The reverse could happen. When the Fulani catch something, they hold onto it. Houser has prayerfully considered what might alter the spiritual course of the Fulani people.

He heard God say one day: "You get Nigerian Baptists to pray for the Fulani, and I will take care of the rest." For three years, Houser has helped Nigerian Baptists focus on the Fulani during the month of prayer.

Mike Stonecypher, IMB liaison with the Nigerian Baptist Convention (NBC) whose home church is First Baptist Church, Glencoe, in Etowah Baptist Association, called this prayer emphasis "one of the most exciting things that I have seen happen in the convention."

What began with a ripple of awareness has spread as Nigerians began to "think beyond their tribal boundaries," observed Larry Taylor, IMB business facilitator in Nigeria. "Mike (Houser) just ripped the covers off and said, ‘Look, these are people who need Jesus. Go. Give. Do whatever it takes to reach the Fulani.’"

Yero was himself a Fulani cattleman who picked up a Christian tract along the roadside. When he converted from Islam to Christianity in 1984, he was forced to leave his family. A missionary discipled him.

Today Yero is pastor of a church and privately disciples new converts not ready to make public decisions. He trains others and assists Houser.

Together they produce radio broadcasts to reach the Fulani for Christ.

Through his veterinary work with the Fulani, Houser builds friendship and trust. His wife, Jennie, focuses on educating their four daughters and assists in operating their farm-home in the West African bush.

Just three years ago, the IMB dug a well for the Housers. Before that, they used rainwater from their home’s roof funneled into a cistern. To conserve, the family of six shared the same bath water. Then that water was collected from the tub to flush the toilet.

When Houser returns from vaccinating cattle, two of his daughters run to greet him. Deborah, 11, opens the gate. Ruthie, 9, jumps on the running board of the white pickup and rides to the house.

Deborah jogs, plays violin and sings alto in their family ensemble. Rebekah, 14, is a future teacher who enjoys art. Elizabeth, 15, is a writer with an interest in nursing.

A few years ago, the Housers posed the question — "Who will pray for us?" — to Nigerian Baptists in the month of prayer focus on the Fulani.

Later, through 200,000 prayer guides in Hausa, English and Yoruba and 20,000 posters, they kept the need before Nigerian Christians. Then Houser took the idea to the NBC with its 8,000 churches and 1 million members.

In a world that functions in individual tribes and language groups, the idea, Taylor said, "is a radical thing. It will be interesting to see how it plays out."

Houser said, "Godly people are Nigeria’s biggest resource. They’re audacious, creative, driven. They are people of remarkable faith. … God is getting them ready. He has them sitting on ‘go.’" (IMB)

Share with others: