When you visit a doctor for the first time, you expect him or her to ask about your past surgeries, illnesses or injuries, but increasingly your doctor might ask questions about your religious beliefs as well.

University of Alabama at Birmingham assistant professor of medicine Mark A. Stafford said he includes questions about a person’s spirituality as part of the five-point “Quality of Life” (QOL) assessment he does. This helps him know how multiple factors, including spirituality, affect a person’s medical condition, giving him a more complete picture of his or her overall health. But he admits there is a reluctance on the part of many physicians to talk about spiritual issues with their patients.

“Studies have indicated for a long time that patients are more interested in talking to their doctors about spirituality than doctors are in talking to their patients about it. The majority of patients say they would like to talk about it,” Stafford said.

Stafford, a Christian, believes in asking about spiritual concerns and says that many physicians whose faith matters to them have been doing so for years. Nonetheless, discussing this topic with a patient can be delicate.

“Doctors have to be very careful about discussing spiritual issues with patients because of the imbalance of power, so there’s a very delicate line in responding to the patient’s concerns and proselytizing,” Stafford said.

He said “healthy boundaries” are vital in the discussion of spirituality. “You have to respect the patients’ boundaries, their autonomy and not impose your value system on them. As Christians, we have to show the love of Christ in the way we accept people where they are,” Stafford said.

The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), has standards addressing spirituality in behavioral health, hospice, hospital and long-term care settings, but they are not the same for each, according to Mark Forstneger, media relations specialist with JCAHO.

In hospitals, standards state the hospital patient has a right to have his or her spiritual values, beliefs and preferences respected, and JCAHO standards require the hospital to accommodate the patient’s right to pastoral and other spiritual services. The organization accredits more than 17,000 health care organizations nationwide. Among them are 4,700 hospitals, JCAHO Web site states.

Nationwide a small but growing number of physicians are taking patient “spiritual histories,” according to Harold G. Koenig of Duke University. By collecting information about each patient’s religious or spiritual beliefs, he believes doctors can make more informed treatment decisions and help patients rally spiritual resources to aid healing.

“Neglecting the spiritual dimension is just like ignoring a patient’s social environment or psychological state, and results in failure to treat the ‘whole person,’” Koenig said.

Koenig described the emerging technique in a manual for health care professionals, “Spirituality in Patient Care” (Templeton Foundation Press).

A spiritual history might include questions such as: Does the patient rely on religion or spirituality to help cope with illness? Is the patient a member of a supportive spiritual community? What spiritual questions, if any, does the patient find most troubling?

Robert Fine, director of clinical ethics at Baylor Healthcare Systems in Dallas, believes spiritual histories can help.

He cited an example of a patient who insisted on aggressive treatment, even though her advanced breast cancer was clearly terminal and she was in terrible pain. Puzzled, her doctors called in Fine, who learned that fear of going to hell kept her from accepting the inevitable. After a conversation with a chaplain, she was able to face death peacefully.

Not everyone agrees with the notion of physicians delving into the spiritual. Some worry that doctors, with their expertise rooted in science, aren’t equipped to navigate the gray areas between faith and medicine.

Jeffrey P. Bishop, who teaches a course on spirituality and medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, said the example of the woman with breast cancer poses tricky questions. Should doctors tinker with a patient’s beliefs, even with the best of intentions? The ends of spirituality and the ends of medicine, he added, don’t always agree — one example being the beliefs of Jehovah’s Witnesses, who refuse blood transfusions even in life-threatening situations.

Nonetheless, he advocates taking patient spiritual histories because he believes that doing so gives patients comfort.

Jeff Flowers, director of pastoral care at the Medical College of Georgia Health System, lectures medical students on taking “patient spiritual histories” as part of a required course on clinical medicine. He urges doctors to use caution.

Some patients won’t want to talk about spirituality and should be allowed room to easily refuse; doctors must tread especially carefully when the patient’s beliefs may seem to hinder medical care.

“I tell the students that we need to honor the person’s right to believe what he or she chooses to believe,” he said. “It’s never our job to dissuade them of their beliefs.” He invites representatives of different faith groups to speak to the medical school class, so that the future physicians can understand that people of less familiar traditions “are not crazy, just devout.”

Koenig estimated that between 5 percent and 10 percent of doctors take some form of spiritual history of patients; he expects the number to grow as graduating students join the field.

Nearly two-thirds of American medical schools in 2001 taught courses on religion, spirituality and medicine. Most doctors don’t take histories, however, due to lack of time or fear of being intrusive.

“Doctors don’t feel comfortable bringing it up,” he said. “We’re at the place we were 20 years ago when doctors were asked to take a sexual history.”

Koenig believes spiritual histories are especially useful with patients facing surgery or life-threatening, chronic or disabling conditions.

With so much recent research pointing to potential benefits of spirituality to physical health, a spiritual history gives the doctor a practical way to harness those benefits.

“If I know a person’s spiritual background, I might ask something like ‘Would a short prayer help in this situation?’” he said. “Knowing that a person is religious frees me to be more forward in using a spiritual intervention that might bring comfort.”

Patient spiritual histories can be useful even when patients and their families are not affiliated with an organized or mainstream religion.

Fine counseled a Wiccan couple struggling with the impending death of their newborn; instead of talking about God, he urged them to think of the baby’s place in the natural order.

Koenig added that the histories allow doctors to counter potential negative effects of spirituality, citing a study suggesting that patients struggling with spiritual crises tend not to heal as well. Doctors can’t help, he said, if they don’t know.

Stafford said that sometimes how persons believes within their faith can cause problems, such as they might feel guilty about being sick — wondering what sins or wrongs they did to be stricken with the illness, when they might have simply caught a germ from someone. (RNS, Anthony Wade contributed)

Increasing number of physicians ask patients about their faith during medical exams

Related Posts

FDA, researchers seek methods of early detection of Alzheimer’s

October 1, 2024

A new blood test could help doctors diagnose Alzheimer’s disease more accurately in a primary care setting, leading to crucial

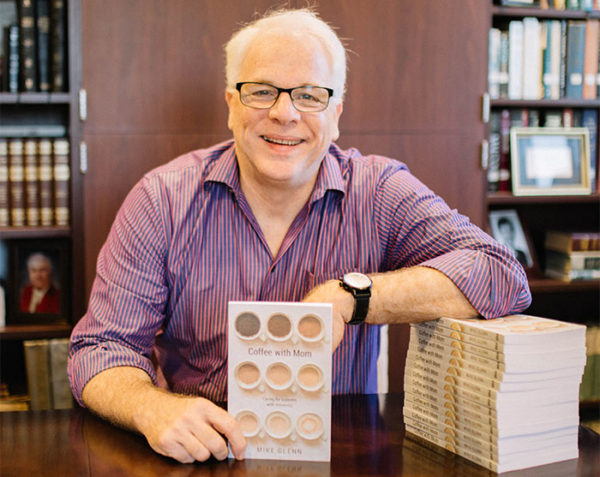

Alzheimer’s, dementia: Pastor shares lessons learned

August 12, 2019

As a minister for more than 40 years, Mike Glenn walked through the valley of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease with

Shame isolates, destroys community, psychiatrist says

October 13, 2016

Nobody needs a psychiatrist to explain what shame feels like — we all know, said Curt Thompson, a noted psychiatrist

Prenatal classes catalyst for new life, faith, churches

January 22, 2015

The young woman gingerly crawls off a motor scooter, grateful for the ride. Before, Kalliyan Seng could make the two-mile

Share with others: