Editor’s Note — This article originally ran Nov. 16, 2017, but recently received a third place award in the feature article, 750–1,500 words category of Baptist Communicators Association’s 54th Wilmer C. Fields Awards Competition. We are reposting it as part of the featured award-winning articles produced by TAB in 2017.

By Grace Thornton

The Alabama Baptist

The dirt road snaked long and lonely out to Cudjo’s cabin on the outskirts of Mobile, and as the car rolled down it, Mary Ellen Caver tried to mentally prepare.

She had lived for years as a single missionary to a tribe in Nigeria before coming home to Alabama. She was used to the unusual.

But she had been told she had a crazy man on her hands.

Many questions

The day before, as she had walked out of a church in south Alabama, she had met a group of black men waiting for her in the parking lot.

They knew she had been a missionary to Africa and they wanted her to put some of their questions to rest.

“There’s a man in our church, and we think he’s crazy,” they said. “He tells all these parables and stories, and he talks in a different language and claims he comes from Africa.”

She told them that even if he was from Africa, the chances of him speaking the same dialect she had learned were one in a million.

They didn’t listen.

And the next thing she knew, the car had rolled to a stop at Cudjo’s gate.

It was the eve of the Depression era when Caver had returned from Nigeria and begun the stateside part of her story, traveling around Alabama leading training sessions for the Sunday School Department. That’s what she had been doing the day the men met her outside the church.

“She traveled all over by bus and would have only milkshakes — she was not going to cost the Alabama Baptist convention a great deal of money,” said Eugenia Brown, who led sessions for the Training Union Department at the time and often ended up at the same events.

Caver took Alabama Baptists’ missions money seriously — she knew that it was those dollars that had sent her to Nigeria and kept her there.

But she had no idea that that money and her missions work would lead to a divine appointment back in Alabama that no one could’ve ever seen coming.

That day at Cudjo’s cabin, Caver swung open the gate, and from his porch Cudjo greeted her in his native dialect.

It was the language of the Dahomey people, the tribe she had been sent to in Africa — the one in a million.

She answered him.

And he erupted with a reply, not to her, but to God: “I thank You, Lord — I knowed You would.”

What Cudjo “knowed” God would do began more than 30 years before when he was a young Dahomey man and found himself on a course he couldn’t change.

Sold and shipped away

The day he was chained to a long, single-file line of other people marching toward a slave ship, he had just had his teeth sharpened. It was a rite of passage for the Dahomey people, the sign he had gone from a boy to a man in his tribe.

But then an enemy tribe captured him, and everything changed.

He was sold and bound for Alabama.

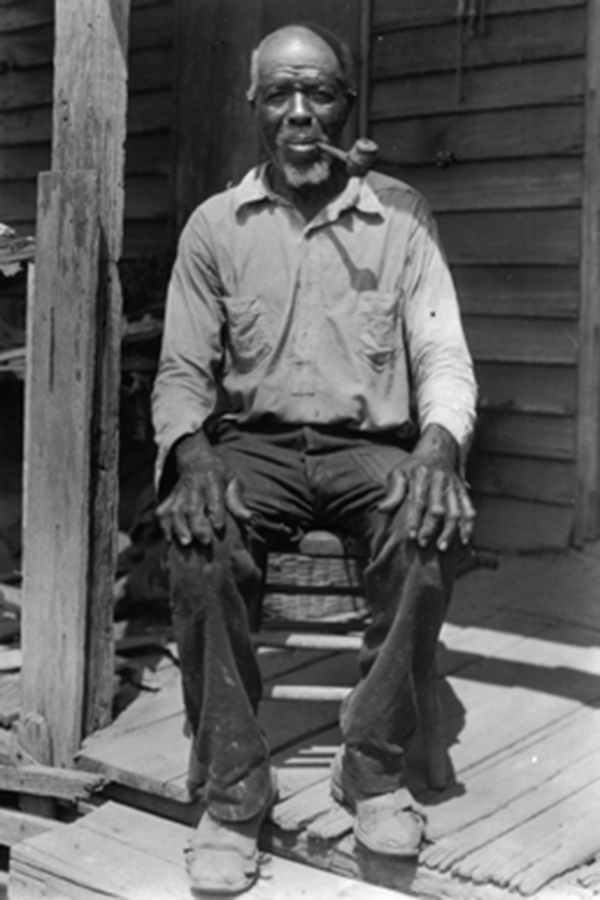

His story would one day be told in the December 1931 issue of National Geographic — he was the last survivor of the last cargo of slaves captured in Africa and sold in the States.

Glimpse of home

The article would tell of how the ship rolled in the swells and crept into Mobile Bay one night to sneak Cudjo and others into Alabama.

And it would tell of how a traveling circus brought the nearest glimpse of home. Cudjo was working in the field with other Dahomey tribesman when they heard the elephants trumpeting as they passed through. Thoughts of Africa swelled in their hearts and they wanted to run after the elephants.

For days afterward, they were happy, Cudjo told National Geographic.

But that fleeting happiness didn’t touch the lifetime of homesickness.

It also didn’t touch Cudjo’s greatest joy — he found Jesus in Alabama.

For decades he had served lighting the lamps and ringing the bell at Union Missionary Baptist Church, the whole time praying that he would live long enough to hear that his people in Africa had heard the gospel.

And then Caver appeared at his gate, telling him that she had been the one to go.

“He asked if she would go in his kitchen and look in the pie safe and get the jar that was in there,” Brown recounted.

“The only thing in that pie safe was a bowl of flour gravy and a jar with coins in it.”

When Caver took the coins to him, he said, “I want you to take these and give them so my people in Africa will know more about Jesus.”

She tried to talk him out of it but he wasn’t swayed. God had done the seemingly impossible — the very thing he had prayed for — and he wanted to give everything he had in return.

One day down the road, at a different training session in Mobile, Caver asked Brown if she would drive her out to visit Cudjo’s grave.

“I said, ‘Who?’ and she (Caver) said, ‘You haven’t heard of Cudjo?’ and I said no,” Brown said. “And she said, ‘Well, he has a beautiful story. You need to hear it.’”

And she told it to Brown.

When they arrived at his grave, they found a crude headstone made out of concrete.

“The information had been scratched on there,” Brown said.

It had his name, Cudjo Kossola Lewis, and the fact that he had been born in Africa.

“It was simple,” Brown said. “And down below it, it said, ‘I believes in prayer.’”

Brown is now in her 90s and Caver has been gone since 1956.

But the “incredible” story of Cudjo’s answered prayer got dusted off again recently when Lonette Berg, executive director of the Alabama Baptist Historical Commission, got a call to pick up some historical mementos for preservation.

“We stored them at the Special Collection at Samford and they included some mementos from Mary Ellen Caver,” Berg said.

One letter from the missions field stood out to Berg and she planned to read it and tell Caver’s missions story at the 2016 Alabama Baptist State Convention annual meeting.

“That was ruminating in my mind when I was down in Owassa one night staying with a friend, Eugenia Brown,” she said. “We were having dinner, and I asked her if she wanted to hear what I was thinking about sharing at convention. I mentioned Mary Ellen, and she said, ‘Oh, I love Miss Mary Ellen. She was such a great lady.’”

‘I was just overcome’

She began to tell Berg the story of Cudjo. She told her about Caver’s trip out to the cabin and she told her about her own trip to the grave.

“It was emotional to hear it,” Berg said. “I was just overcome.”

Brown rummaged around in a drawer and came back with the National Geographic, which had been sent to her by a relative in Texas who gave it to her not because of Cudjo but just because it had a section featuring Alabama.

“God took all these parts from Africa, Mobile, Texas, Owassa and Mary Ellen’s church in north Alabama and put them all together to tell this incredible story,” Berg said. “It’s an amazing, meaningful story. All these parts to me are encouraging — that God is weaving our story, whether it’s big, global things or just a visit with one person.”

Share with others: